Turtle Blog

Saving Baby Turtles Around The World

While the world hunkers down to reduce the spread of COVID-19, sea turtle researchers and patrollers are still out working through the night to protect sea turtles. This pandemic is hitting everyone and many turtle projects depend on volunteers and travelers to support their work.

Our Billion Baby Turtles Fund is now one of the largest private sources of funding for turtle nesting beaches and we are proud to partner with some of the most effective wildlife conservation organizations in the world. These funds are having an impact on the beaches and in the water and none of this would be possible without the support of our generous donors, sponsors, travelers, and other supporters.

Here are some updates from our partners around the world:

Turtle Love Project (Costa Rica)

Photo: Turtle Love Project

Turtle Love Project is a new program in Costa Rica working to protect a previously unpatrolled stretch of beach south of Tortuguero National Park. We provided seed funding for this program through support from the J. Berman Memorial Fund. Starting their work in June 2019, they began nesting patrols, environmental education programs, and community outreach.

Their results from their first year include:

Protecting more than 700 green turtle nests, 12 hawksbill nests, and 14 leatherback nests;

The percentage of nests poached was reduced from more than 90 percent to under 20 percent:

Nearly 60,000 hatchlings were released to the sea; and

Their educational programs reached more than 1,700 local residents and their volunteer program helped three local families.

Tortugas de Osa (Costa Rica)

Photo: Tortugas de Osa

Another new project in Costa Rica (this one on the Osa Peninsula) funded through the J. Berman Fund, Tortugas de Osa works with local residents to patrol nesting beaches including Carate, Rio Oro, and La Leona. This project works closely with the local community, including former gold miners who were looking for alternative livelihoods. This nesting area is one of the biggest areas for solitary olive ridley nesting (as opposed to the arribada beaches) in the region.

In their first season, the Tortugas de Osa team was able to:

Protect more than 3,700 nests, including 52 who were moved to the hatchery, 279 that were relocated, and nearly 2,900 protected in-situ; and

Nests affected by predators (primarily stray dogs) was only 7 percent of all the nests laid on the three beaches.

Grupo Ecologista Quelonios (Mexico)

Photo: Grupo Ecologista Quelonios

This organization founded by Mexican citizens in 1992 has been working to protect one of the most important nesting areas for the critically endangered hawksbill sea turtle in the Western Hemisphere. Located on the Gulf of Mexico side of the Yucatan Peninsula, this project has had extraordinary success in growing their nesting numbers since starting nearly 30 years ago. (Facebook page link here.)

Their success includes:

Nesting numbers have increased nearly 300% since 2011, going from 500 nests to more than 1,400 in 2019.

In the 2019 nesting season, they released more than 140,000 hatchlings to the sea with zero nests depredated by humans or animals.

Fauna & Flora International – Nicaragua

Photo: Nick Bubb / FFI

SEE Turtles has collaborated with FFI Nicaragua since 2013 to protect one of the most important nesting areas for the Eastern Pacific hawksbill at Padre Ramos Estuary, one of the most endangered populations of sea turtles in the world. FFI works closely with the local community to support residents who collect the eggs and bring them to a hatchery for protection. This helps support both the local economy and the conservation of these turtles.

Highlights of their most recent season include:

139 hawksbill nests protected with more than 9,500 hatchlings released;

Nearly 99% of nests were protected, a turnaround from 100% of nests poached before the project began; and

Forty former poachers now employed by the program benefitted from this project’s innovative payment program, which also provides support for community projects.

Our Billion Baby Turtles program had its best year ever in 2019 with the help of these partners and others. In total, we helped save more than 1 million endangered hatchlings by supporting work at 27 important nesting beaches around the world last year, bringing our total to nearly 3 million hatchlings saved to date.

Learn More:

Help save hatchlings with a donation or baby turtle adoption

5 Sea Turtle Success Stories of the 2010’s

Colola Beach, Mexico, Black Turtle Capital of the World

After nearly twenty years of effort, the sea turtles nesting at Colola Beach on Mexico’s Pacific coast, were nearly gone. From tens of thousands of nests in the 50’s and 60’s, their numbers dropped to just 533 in 1999. The black sea turtle (a sub-species of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas agassizi), can be found in the Pacific Ocean along the America’s, and Colola is home to more than 80 percent of their nesting. Some researchers believed they were beyond help.

But a funny thing happened after the turn of the century. Children from the local indigenous Nahua community who were recruited by the University of Michoacan in the early years were growing up to be full-time research staff. People stopped eating turtles and their eggs and exporting them out of the community. Nesting numbers started rising. The twenty years of effort started to pay off as the hatchlings that were saved in the 80’s began to return as adults. Throughout the decade, the number of nests rose to between 3,000 and 8,000 per year (160,000 – 560,000 hatchlings each season).

By 2010, a recovery was evident. Over the decade, nesting at the beach went from nearly 10,000 nests and 650,000 hatchlings in 2010, to more than 45,000 nests and 2 million hatchlings in 2019. That represents a more than 8,000% increase over 20 years, which makes Colola one of the world’s most successful sea turtle conservation efforts. The community and university for these efforts won the Champions Award from the International Sea Turtle Society in 2018. Our Billion Baby Turtles program has supported this program with funding since 2013. (Photo above from Colola by Juan Ma Gonzalez).

Learn more:

Eastern Pacific Hawksbills

The Pacific coast of the America’s for decades was a black hole for information on hawksbill sea turtles. Generally they live in coral reefs (this region does not have many reefs), few nesting beaches were known, and they were not frequently spotted, so many people believed there were too few in the region to invest the energy to protect them. But previously unknown (to the sea turtle community) nesting beaches in Nicaragua and El Salvador were found, and efforts to protect these beaches were launched in the late 2000’s.

The Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative (ICAPO), a network of researchers, non-profits, and local communities, was created to support research and conservation efforts from Mexico to Peru. Researchers discovered that hawksbills in this region live in mangroves, upending long-held beliefs about hawksbills. Now ten nesting beaches and fifteen foraging areas are being protected, representing more than 90 percent of known nesting for this population. There are now believed to be at least 1,000 adult hawksbills in the region. Two major beaches, one each in El Salvador and Nicaragua, are fully protected by conservation organizations (ProCosta in El Salvador and Fauna & Flora International in Nicaragua).

Photo: Eastern Pacific hawksbill from Padre Ramos, Nicaragua (Brad Nahill / SEE Turtles)

The efforts of this growing community of residents, researchers, and others are paying off. According to Michael Liles of ProCosta, “We have flipped the script of the fate of hawksbills in Jiquilisco Bay in El Salvador--the most important nesting site in the eastern Pacific--going from 0% of hawksbills nests protected in 2007 to over 95% protected in 2018." For these efforts, ICAPO received the Champions Award in 2016 from the International Sea Turtle Society. Our Billion Baby Turtles and conservation travel programs have supported these efforts since 2011.

Learn more:

Florida’s Stunning Sea Turtle Comeback

Dozens of organizations and government agencies have been working on Florida’s coast to protect sea turtles for decades. While the leatherback, loggerhead, and green turtles nesting on this state’s beaches don’t have the levels of pressure from people eating eggs and turtles as in many other places, they face a variety of challenges. Coastal development, including beach lighting, furniture, pollution, and coastal armoring, is evident throughout the state. Large numbers of tourists can impact nesting beaches, generate a lot of trash, and bring their boats and vehicles.

With these challenges and others, the recovery of the green and loggerhead nesting in Florida has been dramatic. 2019 was a banner year for the state’s beaches, with more than 50,000 loggerhead nests and 40,000 green turtles nesting on index beaches that are tracked by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The 2019 green turtle totals were a record and loggerhead nesting set a record in 2016 with more than 60,000 nests. Compared to the 2000’s, where green turtle peak nesting ranged from about 5,000 to 10,000 nests, the 2010’s were an extraordinary decade, with four years each passing 25,000 nests. Loggerhead nesting, which had dipped to 30,000 to 40,000 nests per season in the 2000’s after ranging from 40,000 – 60,000 in the previous decade, rebounded to similar numbers in the earlier decade.

Learn more:

Ending the Tortoiseshell Trade in Cartagena, Colombia

Cartagena, Colombia, is an extraordinary mixture of cultures with a fascinating history. From a Spanish colony founded in 1533, it has become a major tourist destination, home to the largest fortification in the Spanish colonies (San Felipe Castle) and a well-preserved historical area known as the “Walled City.” More than 3 million travelers visited this city in 2018, making it one of the country’s top destinations. Unfortunately for sea turtles, products made from hawksbill shells (aka tortoiseshell) has been a popular souvenir and the city has developed a reputation of being a hub for this illegal trade.

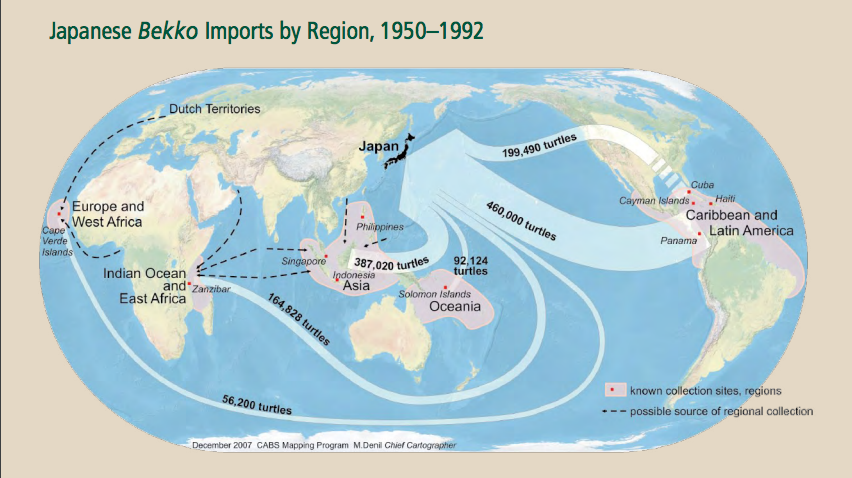

The tortoiseshell trade has devastated populations of hawksbill turtles around the world. An estimated 9 million shells were exported to Japan from 1844 to 1992, according to a recent study by Monterey Bay Aquarium. Hawksbills are now considered critically endangered with estimates of adult females worldwide ranging from 15,000 t0 25,000. In Cartagena, research by Fundacion Tortugas del Mar, a Colombian conservation organization, showed that from 2008 to 2013, around twenty stores and vendors sold an average of 2,500 products per year. The city was identified as the second largest hotspot for this trade in the 2017 report Endangered Souvenirs, published by our Too Rare To Wear campaign.

Tortoiseshell for sale in Cartagena (Fundacion Tortugas del Mar)

Fortunately for the hawksbills, the hard work of organizations led by Fundacion Tortugas del Mar, along with WWF Colombia and others, in partnership with city officials and law enforcement agencies have reduced the trade in the city by an estimated 80 percent. Frequent police patrols have reduced the number of tortoiseshell products found from an average of 2,000 per year to around 200 or fewer products the past two years, according to research by the Fundacion. This success comes from a combination of collaboration between conservation organizations and local authorities, outreach and education, and recruiting souvenir shops to be certified turtle-free by the Fundacion. Too Rare To Wear has worked with Fundacion Tortugas del Mar on this effort since 2016.

Learn more:

Recovery of Hawksbills in the Atlantic and Caribbean

As mentioned above, the tortoiseshell trade has decimated hawksbill populations around the world, and the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico populations were among the hardest hit. According to data from the most recent hawksbill Red List assessment by the IUCN, approximately 660,000 shells were exported to Japan from 1950 to 1992 (though the recent research by Monterey Bay Aquarium shows that may be significantly underestimated). With this trade, nesting beaches from Mexico all the way to Colombia and throughout the Caribbean islands dropped dramatically.

The tide for hawksbills started to turn in the early 90’s, when Japan finally ended its legal tortoiseshell trade for good through the CITES trade. This did not end this trade (see previous section) but did represent a turning point in efforts to protect this species. Now, nearly thirty years later, we are starting see the results as a generation of turtles that avoided the trade matures, though local challenges like hunting of hawksbills and illegal collection of eggs persist.

Two nesting beaches in the region are particular bright spots, one in Panama and one in Mexico and have grown dramatically due to the hard work of researchers and local communities to reduce illegal collection of eggs and adult turtles. In Panama, according to research carried out by Annie and Peter Meylen in conjunction with the Sea Turtle Conservancy, nesting in the Zapatilla Cays area in the Bocas del Toro archipelago has grown nearly 500 percent since 2006, to more than 1,000 nests in 2018 and have surpassed 100,000 hatchlings produced the past two seasons.

On Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, two groups have been working to protect hawksbill since the early 90’s, Pronatura Peninsula de Yucatan and Grupo Ecologista Quelonios. In the early 2010’s, Quelonios averaged between 400 to 500 nests (45,000 to 55,000 hatchlings) but through the decade those numbers grew to more than 1,000 nests each year in 2017 and 2018 (more than 100,000 hatchlings per season). Pronatura has also seen a major increase in hawksbill nesting at several beaches, with Holbox surpassing 1,000 nests in a season for the first time and two other beaches showing significant growth (Celestun and El Cuyo). Our Billion Baby Turtles program has provided financial support for both of these projects, Sea Turtle Conservancy in 2019, Quelonios since 2018, and Pronatura since 2017.

Learn more:

These success stories show that communities working with conservationists, researchers, and government agencies can significantly reduce threats that turtles face and bring endangered species back from the brink. Many threats to sea turtles persist and new ones are emerging, but with collective efforts, the recovery of sea turtles around the world can continue. A big thanks to everyone out there who contributed towards these success stories!

Turtles, Turtles Everywhere

I’ve been working with sea turtle conservation partners for the past decade to provide support to important nesting beaches around the world. I’ve worked personally on four different nesting beaches in Costa Rica and have visited dozens of others. I’ve never seen anything like the sheer avalanche of sea turtles and hatchlings that Colola Beach in the Mexican state of Michoacan, which is known as “The black sea turtle capital of the world.”

I just wrapped up bringing two groups of a total of 25 people to volunteer on this extraordinary beach. The numbers are overwhelming; 46,000 nests last year with more than 2 million hatchlings alone. Over the ten days that I spent at this beach with these groups, there were more than 3,200 nests and roughly 20,000 hatchlings. The beach is one long undulation of holes made by the nesting turtles.

Walk along the beach during the day and you’ll see them nesting close to shore. Look down and you might come across some straggler hatchlings from a natural nest. Head to the hatchery at dusk and you’ll find little heads popping out of several nests. Wait an hour and you’ll have a dozen nests hatching at the same time, where hundreds of baby turtles are released to the water at the same time. Walk a couple hundred feet onto the nesting beach around 9 pm and most nights during this time of year, you’ll find five or ten females right there in front of the hatchery nesting. One night, while watching a female nest, a natural nest hatched about two feet away, dozens of little hatchlings scrambling around my feet in a matter of minutes. Get up at dawn and you’ll usually see at least a couple of late-night nesting turtles returning to the ocean.

The situation wasn’t always this way at Colola. After decades of harvesting of the adults and eggs for export, this population crashed. What once numbered in the tens of thousands, this population had just an estimated 500 females in the late 90’s. But the fruit of efforts starting in the late 70’s and early 80’s by biologist Kim Clifton and researchers from the University of Michoacan started paying off. With each year the number of nests climbed steadily, from a low of 533 in 1999 to now more than 40,000 per year, a stunning recovery.

Researchers including Carlos Delgado, who started working at Colola 30 years ago, began working with the local Nahua community, an indigenous group that lives along this stretch of coast. They hired adults to help monitor the beach and paid kids to bring nests to the hatchery to be protected, many of whom now work on the project as adults. Once the hatchlings had time to grow, their numbers rebounded and this is now one of the biggest sea turtle success stories in the world.

These two trips were organized as an opportunity for our past travelers to have a special experience on a beach that our Billion Baby Turtles program has been supporting since 2014. A total of 25 people from the US and Canada spent five nights each at the research station to see and work with the black sea turtles. And turtles did they see!

The turtle routine started in the early evening; as the sun set, the hatchlings would start emerging from nests in the hatchery. Batch by batch, our volunteers brought them to release near the water, leaving them to cover the last ten or twenty feet on their own. Around nine, groups would head out to the beach to study the adult females, collecting information on their length, where they nested, and their tag numbers as well as collecting eggs to bring to the hatchery.

Each day, we headed to nearby beaches as beautiful as any in Mexico. Hanging out under thatch roof shelters, we took turns swimming and snorkeling, swapping stories of visits to other nesting beaches, and enjoying local snacks and beverages. Each group visited a family in the nearby town of Maruata that made ceramic art by hand, digging the mud from around their houses, refining it, shaping it into various shapes (including turtles of course) and then firing them in their kiln for hours to finish them. Another day, we took a nature walk with a local Nahua elder who showed us plants used to cure infections, for upset stomach, healing wounds, and more. We also learned about native trees used for wood and natural dyes. Among the wildlife we saw were iguanas, egrets, ibis, a baby hummingbird, and several colorful butterflies. We also visited the Finger of God rock formation in Maruata, a gorgeous stretch of coastline.

Hummingbird fledgling

Finger of God in Maruata

Our second group coincided with one of the largest celebrations in Mexico, the “Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe” (Virgin of Guadalupe Day), December 12th. The original story goes back to early colonization in 1531, when a pilgrim named Juan Diego saw the apparition of the Virgin Mary, who told him to go to Mexico City (then Tenoctilan) and tell the bishop at the church. When the didn’t believe him, he returned to the pass and spoke again to the virgin to get proof of her existence. The virgin told him to bring rose petals bound up in his clothes to the church; when he dropped them in front of the bishop, the image of the virgin was left in the imprint of his clothes. This frock can still be seen at the basilica named in her honor in Mexico City.

We were invited to visit the beginning of the festivities in a nearby Nahua town. Loud fireworks went off as we arrived, a creative way to call surrounding locals to the party. A group of girls dressed in traditional dress did a series of dances, one right into the other without breaking a sweat in the intense heat. Hundreds of pounds of corn meal were expertly being converted into tortillas as we watched (pro tip, rub lime juice and salt on tortillas before you eat them).

Our second group had the opportunity to participate in research in the hatchery, helping to dig up nests two days after they hatched. The remaining eggs, shells, and hatchlings (some surviving, some not) are analyzed to determine how well the hatchery was functioning. Once the hatchlings were released, we were done our turtle work for the week.

Due to conflict in other parts of Michoacan state, tourism declined dramatically in this part of Mexico, though the beach area remains safe. The economic impact of these two groups on the community is significant; more than US $12,000 was spent in and around Colola, an area with few economic opportunities. In addition, our Billion Baby Turtles program gave a $10,000 grant given to the project by, which was partially funded by this trip. Our two groups also completed roughly 125 volunteer shifts in the ten days.

Spending two weeks at Colola was a profound experience. Seeing a truly successful conservation project at work is energizing and holds many lessons for projects around the world trying to duplicate their accomplishments.

Learn more:

A New Tool To End the Turtleshell Trade

Hawksbill sea turtles are among the most endangered sea turtle species, considered critically endangered by the IUCN. One of their top threats is being killed to make products out of their shells and they are the primary turtle species that faces this threat. Despite the end of the legal international commercial trade of hawksbill shells through the CITES treaty, the domestic trade in handicrafts remains a major threat to these turtles around the world, especially in Latin America and Asia where enforcement of laws is often non-existent.

The shells are crafted into souvenirs to sell to foreign tourists including jewelry, guitar picks, combs, and other items. A recent study estimated at least 9 million shells were shipped to Japan from the 1840’s to the 1990’s when the legal trade ended, resulting in just an estimated 15,000 – 20,000 adult females worldwide today.

Despite the trade being banned for decades, the tortoiseshell trade continues to threaten the critically endangered hawksbill sea turtle around the world. Our Too Rare To Wear program works with the tourism industry and conservation community to help end the trade of tortoiseshell products around the world. One of the challenges with ending this trade is that these products are often hard to distinguish between real tortoiseshell and similar looking products like faux tortoiseshell, horn, bone, or other types of shell. This makes it difficult for travelers, enforcement officials, or online marketplaces to know what they are looking at.

Real (photo: Hal Brindley)

Fake (photo: Brad Nahill)

Too Rare To Wear is partnering with Alex Robillard, a predoctoral student working at the Smithsonian Data Science Lab, on a ground-breaking new project that will help governments, online retailers, conservation organizations, tour operators, and travelers to identify and report when these products are being sold. This model will use machine learning to distinguish tortoiseshell products from those that are similar or replicas with a high degree of accuracy. We will use a set of photos of both real and similar products to train the model what to look for. Users will be able to upload photos of products taken online or while traveling and receive confirmation if the product is tortoiseshell. The phone app will also record location of the products, which will support research into the trade and provide information to enforcement authorities.

Applications of this model will include:

Allowing travelers, tour guides, and others to identify which products to avoid purchasing while traveling;

Helping efforts by enforcement officials around the world to identify these products for sale in markets, online, or at borders;

Online retailers can use the model to determine when people are illegally offering these products for sale on their platforms;

Conservation organizations can quickly and simply collect information on this trade instead of time consuming and inefficient paper surveys.

Too Rare To Wear

The goal of Too Rare To Wear is to reduce demand for turtleshell products through the tourism industry. We do that by educating travelers on how to recognize and avoid these products, by studying and publicizing the current trade, and by partnering with organizations based in hotspots for this trade to do outreach, improve enforcement, and study this trade. The project works with more than 100 tour operators and 50 conservation organizations around the world, published reports on the global tortoiseshell trade, and created a simple guide to recognizing these products that has been translated into five languages.

Kids Working To Save Baby Sea Turtles

One great way that kids can contribute to protecting sea turtles is by raising funds. Our Billion Baby Turtles program supports more than 20 organizations working to protect sea turtles and hatchlings on some of the world’s most important nesting beaches. For every dollar that students raise, we can save at least 10 endangered hatchlings; to date, students around the world have helped to save more than 300,000 baby turtles! Many students raise funds and awareness by promoting alternatives to single use plastic, since plastic bags, straws, and other products are a threat to sea turtles.

There are two ways that students can raise funds anytime of the year, either through class fundraisers or school or on their own. Students can also participate in our annual Baby Turtle Fundraising Contest, which takes place in October and November every year.

Elizabeth & Natalie

Sea Savers

For about a year cousins Elizabeth and Natalie had been helping their families to use less plastic and decrease their waste. Both girls were saddened to learn about how plastic affects sea creatures and the impact it has on the earth. They started praying every night that the people who are trying to save the ocean would actually be able to save it. Their parents started reminded them that by reducing their plastic waste they were people trying to save the ocean. The girls thought about this and decided that together they could do more to save the ocean. As such, they decided to form Sea Savers to encourage others to use less plastic, raise money to help sea creatures, and help clean up the ocean.

To start, they created a website and slideshow to further explain the impact of plastic and simple changes people could make. To raise money, they ordered Pura Vida bracelets in custom colors to look like the ocean. They decorated notebooks with pictures of turtles, dolphins, and narwhals, and why it is important to use less plastic. With these and a few additional items they sold their products to family and friends, had a table at a garage sale, and even a stand at the local Farmer’s Market. At the end of their first fundraising session they had raised enough to save 5,000 baby turtles and to support two additional organizations that focus on cleaning up the ocean.

Alex, Emma, and Maeve

Alex, Emma, & Maeve

Alexa, Emma, and Maeve are a group of 4th grade girls who live on Long Island in New York. As a fundraiser, they decided to sell friendship beads on the beach in Fire Island to save the turtles. They raised $79.50 in 3 hours, enough to save about 800 baby turtles!

The SteelTurtles crew

SteelTurtles

Students from Kettle Moraine High School in Wales, WI did a ‘Make a Difference’ project. For this project, the students chose to combat plastic waste, specifically with plastic straws. They bought 200 stainless steel straws and sold them at a local event, and sold out! They made over $500 that was donated directly to save 5,000 baby turtles. They were so encouraged by this that they decided to make a business and named it SteelTurtles. SteelTurtles now has the mission to create 0% waste with plastic straws and to protect our oceans.

Trevor and Maddox

Trevor and Maddox

Trevor and Maddox raised $130.00 for the sea turtles as part of a school empathy project. They planned out how they were going to raise money in school. They made informational flyers to hand out to businesses and residential homes to spread awareness about saving the sea turtles. They also set up a Go Fund Me account to easily collect money and made T-shirts for the boys to wear while handing out flyers. The boys were very happy that they saved 1,300 sea turtles!

Annabel

Annabel

After having read articles and watched videos about the harmful impact of plastic pollution on marine biodiversity, Annabel was motivated to support an organization that would campaign against the use of plastic straws and protect endangered baby sea turtles. She has always been in awe of sea turtles, having seen them on snorkel trips in Costa Rica and Guadeloupe.

Annabel and her friends Brooke and Sami were therefore very excited to learn about SEE Turtles, and together they hosted an ice cream and lemonade stand fundraiser last spring. Inspired to continue this mission, Annabel decided this past summer to channel her love for DIY art projects towards another fundraiser for SEE Turtles, through a stamp magnet making business. She created sets of whimsical stamp magnets on wood discs made with colorful glittered embossing powder. She raised $70 through the sale of over 80 homemade magnets, which she sold to family, friends and neighbors. Annabel hopes to continue to support the organization through other handcraft businesses in the future.

ProCosta: Protecting El Salvador's Unique Hawksbill Turtles

Hunted for their colorful shells, hawksbills are among one of the most endangered sea turtle species. They live in tropical waters around the globe and a decade ago, the world almost lost this turtle in the entire eastern Pacific Ocean. Yet, thanks to committed conservation organizations, including the Salvadoran organization ProCosta, hope exists for their continued survival.

The hawksbill is named for its narrow head and sharp bird-like beak, which helps them feed on their favorite meal — sponges. Of the seven marine turtles, they are on the smaller end, ranging between 100 to 200 pounds and reaching up to three feet. Considered critically endangered by the IUCN, they are estimated to have only about 15,000 – 20,000 breeding females left on the planet, and in the eastern Pacific they number fewer than 700.

Eastern Pacific Hawksbill - photo by Allison Shelley / Wild Earth Allies

Their most important nesting beaches are found on the southeast coast of El Salvador in Jiquilisco Bay, a coastal estuary lined with mangrove trees. It’s such an important site that in 2005 it was designated a Ramsar wetland and in 2007 it was named a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Combined with other sites in nearby Nicaragua, they account for 80% of the known nesting for this species in the eastern Pacific.

Before 2007, the scientific community didn’t even know if hawksbills still existed in the Pacific coastal region of the Americas. Then, ProCosta founders (previously a project of the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative or ICAPO) found active nests and feeding grounds. The nonprofit project officially launched in 2008 and since then, ProCosta has led hawksbill research and recovery efforts in Jiquilisco Bay and other parts of El Salvador.

The program has been a success. In a country that is the most densely populated in the region and has few endangered species left, the effort to bring the hawksbill back has captured the country’s imagination. In 2007, more nearly 100% of the nests were being collected to sell on what was then still a legal market. To combat this threat, ProCosta turned to the community. They converted the local egg-collectors into egg protectors, by safely raising eggs in protected hatcheries. The government made eating turtle eggs or meat illegal in 2009.

ProCosta egg hatchery - photo by Allison Shelley / Wild Earth Allies

Releasing hatchlings in Jiquilisco - photo by Allison Shelley / Wild Earth Allies

Since 2011, over 95% of nests are now protected in Jiquilisco Bay. In 2018, for example, a record-setting 295 nests were protected and 27,855 turtle hatchlings were released into the ocean. With 115 egg-collectors participating in the program, about 170 local families benefited from the work of ProCosta. Most recently, ProCosta outfitted year-old turtles with satellite tags to better understand their movement patterns, the latest in what has been a decade of ground-breaking scientific research at this site.

“It is incredible to think that just 10 years ago hawksbills in the eastern Pacific Ocean were considered virtually absent and beyond hope of recovery,” says Mike Liles, ProCosta President and sea turtle researcher. “Since then, not only is there renewed hope, but together with coastal community members we have made enormous strides to make recovery a reality.”

SEE Turtles has played a part in that success by funding the nesting beach work, as part of our Billion Baby Turtles initiative. The funds support the egg collection program, paying the collectors to bring the nests to a protected hatchery, where they are watched until they hatch and then released to the ocean. This was the first project that SEE Turtles helped to fund, raising $5,500 and saved 11,000 hatchlings that season. As of 2019, we’ve given a total of $45,000, which has helped this organization save roughly 91,000 baby hawksbill sea turtles! We have also run teacher workshops with the organization, helping to train local educators about sea turtles, and have provided funds to get hundreds of local students involved in the efforts.

“With the consistent support of Billion Baby Turtles, we have flipped the script of the fate of hawksbills in Jiquilisco Bay in El Salvador--the most important nesting site in the eastern Pacific--going from 0% of hawksbills nests protected in 2007 to over 95% protected in 2018," says Liles.

The Return of The Black Turtle

Today, we’re flooded with hopeless headlines of disappearing ecosystems and endangered wildlife. Yet, along the remote and rugged coastline of Western Mexico, a population of black sea turtles has recovered from near extinction, thanks to the Black Sea Turtle Recovery Program. In fact, it’s one of the most successful wildlife conservation programs in the world — and SEE Turtles helped.

Considered by most experts as a subspecies of the globally ranging green sea turtle, the black sea turtle occurs only in the eastern tropical Pacific. The black sea turtle population is currently doing well, but that wasn’t always the case. “This turtle was close to extinction in the 1960’s and 1970’s due to the intensive harvesting of reproductive adults and nearly all of the eggs laid along the coast,” says biologist Carlos Delgado from the University of Michoacán.

By the 1970’s, it’s estimated that an average of 70,000 eggs per night were taken and harvested during the peak of the nesting, at about 20 pesos per 100 eggs. The number of nesting females went from an estimated 25,000 in the 1960s and 1970s to perhaps as few as 170 by 1988.

To save this turtle, something needed to change.

The Road to Recovery

So, in 1982, the Michoacán University, indigenous communities from Maruata and Colola, and national and international institutions started a project to recover the black turtle population of the Michoacán coastline. “Colola Beach is the most important nesting site for the black turtle in Mexico,” says Delgado. It hosts more than 75 percent of the world population of black turtles.

The first part of the program was to keep people from collecting the eggs. To do that, the University of Michoacan biologists set up hatcheries every nesting season at Colola and Maruata. Members with the project would patrol the beach at night, collect eggs and transplant them to new nests dug in a hatchery. Once the hatchlings emerged, they were collected from the pens and then released from the beach to crawl to the sea.

The next part of the effort was to involve the local community in the conservation process. For instance, for centuries the black sea turtle was an important food source for the Nahua indigenous group on the Michoacan coast. Yet, it was no longer sustainable. One of the goals of the recovery program was to help the local people find alternative sources of food, such as iguana farming and family gardens. Additionally, the adult turtles and their eggs were an important source of income. So, the project developed an ecotourism program to view the nesting turtles, with profits going back to the local community. The idea was to make living turtles worth more than dead ones.

Shellebrate Success

In 1999, this project had a low of just over 500 nests. But starting in 2,000, nesting numbers began a steady climb upward due to the efforts of the community and researchers, combined with a ban on hunting turtles in Mexico in the 1980’s. The past two seasons have been the best in decades, averaging more than 30,000 nests. The average number of nesting females has increased from a low of about 500 individuals to more than 10,000 as of 2016. Their population is now considered one of the 12 healthiest sea turtle populations in the world.

Nesting black turtle

Black turtle hatchery

SEE Turtles has played a part in that success by funding the nesting beach work, as part of the Billion Baby Turtles program. The funds go towards paying local residents to patrol important turtle nesting beaches, protecting turtles that come up to nest. In 2013, the first year we worked with Colola, we gave the project a $3,000 grant, which helped save 40,000 hatchlings. As of 2019, we’ve provided a total of $42,000 in funding which has helped to save more than 1.3 million hatchlings at this important beach! We plan to increase our support and benefit the community through offering new trips to participate in this inspiring program.

“The recuperation of the black turtle has been made possible due to the support of organizations like SEE Turtles who have committed to restore this sub-species to its historic levels,” says Delgado.

Photo credits: Carlos Delgado / University of Michoacan

SEE Turtles Wins 2019 World Travel & Tourism Council's Changemakers Award!

The World Travel & Tourism Council announced SEE Turtles as the winner of the 2019 Changemakers Award at the Tourism for Tomorrow Awards ceremony. The Awards, now in their 15th year, took place at a special ceremony during the WTTC Global Summit in Seville, Spain, to celebrate inspirational, world-changing tourism initiatives from around the globe.

The 2019 WTTC Tourism for Tomorrow Award Winners are highly commended and recognized for business practices of the highest standards that balance the needs of ‘people, planet and profits’ within the Travel & Tourism sector. New to 2019, the Changemakers Award is for a Travel & Tourism organization which has made real, positive, and impactful change in a specific area of focus defined by WTTC. This focus will change each year. This year the award shone a spotlight on fighting the illegal wildlife trade through tourism.

“SEE Turtles is thrilled to have our efforts to reduce the illegal trade in sea turtle shells and eggs recognized. Our hope is that this award will help to reduce demand for this trade and expand our campaign with the tourism industry. It is an honor to accept this award on behalf of our partners around the world and we thank our donors, sponsors, travellers, and others who helped us get to this point,” said SEE Turtles President & Co-Founder Brad Nahill.

SEE Turtles is an organization that supports sea turtle conservation throughout Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. Since 2008, by support on-the-ground efforts to protect sea turtles throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, SEE Turtles has helped saved more than 1.7 million hatchlings through the Billion Baby Turtles program and educated over 10 million people and creating a coalition 130+ tourism companies and conservation organizations working to end the demand for turtleshell through their Too Rare To Wear campaign.

The Awards are judged by a panel of independent experts, led by Prof. Graham Miller, Executive Dean, Professor of Sustainability in Business, University of Surrey. The panel included academics, business leaders, NGO and governmental representatives who narrowed down the list of 183 applications to just fifteen finalists. The three-stage judging process included a thorough review of all applications, followed by on-site evaluations of the Finalists and their initiative.

WTTC represents the global private sector of Travel & Tourism. Its Global Summit is the most important event in the sector worldwide each year.

For more information on the Tourism for Tomorrow Awards and all the Winners, please visit http://wttc.org/t4tawards

Help Us Celebrate!

Students Saving Sea Turtles

Kids love sea turtles. I’ve given presentations to hundreds of kids around the US and one of my favorite parts of my job is seeing their faces when they see and learn about these animals and ask questions about them. Students are a big part of how we save hatchlings through our annual Billion Baby Turtles School Fundraising Contest. This year, more than 200 students at 9 schools helped to raise more than $3,000 to save over 15,000 endangered turtle hatchlings at important nesting beaches.

2018 was the sixth year we have run this contest and it’s impact has been huge. Roughly 1,900 students at dozens of schools have helped to raise about $25,000, resulting in the saving of an estimated 125,000 baby turtles! For their hard work, students receive prizes from our sponsors, including Endangered Species Chocolate, Nature’s Path/EnviroKidz, EcoTeach, Pura Vida Bracelets, Eartheasy, and others.

Here are a few of the inspiring efforts undertaken by classes this year to help save turtles:

· Jefferson Elementary (Missouri): The class wrote commercials promoting donating during Sea Turtle Week. The students shared facts about turtles and why they are in danger and they were recorded giving them in front of a green screen. The students also made a sea turtle fund collecting machine, which is a container made from various materials like milk jugs, wall paper from wall paper books, and cardboard that sat in the classrooms. The students would go collect it and bring the money back to class and then deliver postcards for donations. Jefferson has participated in the contest since 2014 and have won prizes every year since then.

· Middle School at Parkside: Two art classes with 47 students worked together to hold a bake sale, sell our hatchling postcards, and sell coffee to teachers to raise funds. All together, they raised $350 that will help save 1,750 hatchlings and were runners-up winners in the contest. This effort was part of a lesson called “Bringing Awareness to Endangered Species with Art” where students will display their art (some of the great examples below). This was Parkside’s first year participating in the contest.

· Jefferson Elementary (California): These students gave up their lunch recess for a week to make which were hung all over the school. We spent an additional lunch recess reviewing sea turtle facts and how the project helps protect sea turtles. I had 2-3 students sign up on a calendar to help me sell post cards and stickers every morning before the school day started. We had a little cart that had a simulated sea turtle nest (large bowl filled with sand) and eggs (ping pong balls). The students would explain that sea turtles lay their eggs on the beach and that the ping pong balls were about the size of the eggs and identified the species of sea turtle on the postcards and give a few facts. The “Sea Turtle Ambassadors” have participated and won every year since 2014.

Jefferson Elementary (CA) Sea Turtle Ambassadors

Extreme Turtle Sex: The Exhausting Life of the Black Sea Turtle

“The turtles here do what we call ‘extreme sex’,” Carlos Delgado tells me with a wry smile. Responding to my raised eyebrows, he goes on to explain that the fornication happens near the intense wave breaks, often resulting in a rather dramatic coitus interruptus. Adding to the thrill of the danger is the (perhaps not surprising) behavior of the male turtles, who can outnumber the females five or six to one (no need here for Turtle Tinder). Carlos described the carnal embrace as we looked over the coast from a large rock at one end of the beach. I felt a twinge of voyeur’ s guilt as I leaned against a large cross at the top of the rock in my efforts to capture the act with my zoom lens.

The randy males fiercely compete with each other to join the party, to the point of actively (shamelessly?) working to disengage the large tails of the more successful competitors from their female partners. In their hormone-filled frenzy, males often mount each other (we’re not judging). It is, as our co-founder Dr. Wallace J. Nichols describes it in this article, “a bizzarely orgyastical circus of ancient oceanic sexuality.”

Carlos, a biologist with the University of Michoacan, has been researching the black sea turtle, considered by many experts (though perhaps not Carlos himself) as a sub-species of the green turtle. The work on the beach is led by members of the indigenous Nahua community, who take great pride in their contribution to this success story; the local kids patrol the beaches each evening during nesting season and bring the eggs to a hatchery where they are watched over until hatching roughly two months later.

Despite their lack of grace and propriety (and seemingly poor choice in location), these turtles seem to be pretty effective lovers. The recovery of this population is clearly one of the biggest success stories in the world of sea turtles (and perhaps all of wildlife conservation.) In the 60’s and 70’s, large number of eggs and turtles were consumed here. The conservation effort started at this beach in 1982 by Javier Alvarado Diaz and from a low of roughly 500 nests in 1988, 2017 was their best nesting season to date, with more than 30,000 nests (!) and 1.8 million hatchlings released, a growth of about 3,000 percent. Our Billion Baby Turtles program contributes to the extraordinary effort of the Nahua and University of Michoacan researchers; our funding since 2013 resulting in roughly 900,000 hatchlings being protected.

The inevitable result of all that sex (photo: Carlos Delgado)

The work on the beach is supported by work happening where these turtles feed and grow, off the coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. The Grupo Tortuguero, a network of fishermen, scientists, community members, and others, have been working to study and protect these turtles for more than 20 years. Grupo Tortuguero works closely with RED Travel Mexico to promote alternative sources of income for coastal communities and fund research efforts. Travelers can participate in this research on our Baja Ocean Wildlife Expedition, run by RED in partnership with Grupo Tortuguero.

While on the way to Colola, Carlos, Omar (a geneticist working with Carlos), and I made a quick stop at Ixtapilla, an olive ridley “arribada” beach about 20 minutes north. If the black turtle was talented at reproduction, they can’t hold a candle to the olive ridley, who nest in the tens of thousands over a few days several times a year. I can’t imagine what their mating looks like but I’m sure it’s no prettier than the greens. Even in the middle of the day, in between arribadas, there were a few females finishing their nests and heading back to the sea. The beach was littered with fragments of old eggs, the hatchlings long having made their way to the water (or the stomachs of vultures).

Olive ridley at Ixtapilla

At the Colola research station, my hosts cooked up the largest red snapper I’ve ever seen, splitting the fish in half, covering it with a mix of tomato sauce and veggies including tomato, onion, and pepper, and grilling it over charcoal (a local specialty called “zarandeado”). It was as delicious as it sounds. Afterwards after dusk, we took a bunch of olive ridley hatchlings out to the beach for release. As they slowly made their way to the water, a young man came running down the beach, headed who knows where. Carlos was unable to stop his Godzilla-like rampage through the baby turtles, resulting in one being firmly planted several inches into the sand (though it seemed to be ok and continued its plod once pulled out of the footprint).

That night, we headed out by quad to look for nesting turtles. We quickly came across a set of tracks heading up the beach and checked to see what phase of nesting the turtle was in. The female was still looking for a spot to nest, so we hopped on the quad to cover the rest of the beach before heading back. The turtle by then had barely started to dig its body pit, deep enough to completely hide the turtle below the level of the surrounding beach.

As if the mating portion of their life cycle wasn’t exhausting enough, Carlos explained that the black turtle has an extremely long nesting process, taking an average of 3 and a half hours from exiting the water, to finding a spot, digging out the pit, digging the nest, depositing the eggs, camouflaging the spot, and heading back to the water (the longest of any sea turtle). They can go way up the beach (up to 150 meters / 500 feet), requiring an extraordinary amount of energy. They do this a couple of times a season, another testament to the unstoppable will of females of all species.

The extraordinary recovery of the black turtle is a source of pride for the residents and researchers that have spent decades working to get to this point. Their efforts recently resulted in winning a Champions Award from the International Sea Turtle Society, where photos from this beach stunned the largest gathering of sea turtle experts from around the world. This story was also covered in a fantastic photo essay by our good friend Neil Osborne in Orion Magazine.

Photo by Neil Ever Osborne for Orion Magazine

While this success story provides hope for other sea turtle nesting beaches, more extreme sex is needed to bring the black turtle back to historic levels. From an estimated 25,000 females nesting here before the decline in the 60’s and 70’s, the population is now back to roughly 10,000 nests. Even now after these impressive results, CONANP (the National Commission of Protected Areas) is proposing to cut the size of the sanctuary in half, which Carlos and his colleagues are working to prevent.

But even though there remains a way to go and challenges persist, the future of the black turtle looks bright, a welcome beacon of hope for these ancient reptiles.

Learn more:

Sea Turtles Get It On, And On… by our co-founder Dr. Wallace J. Nichols

Tortuga Rising: Photo essay of the black turtle by Neil Ever Osborne

Ending The Turtleshell Trade in Colombia

“I love hawksbills but I prefer to see them alive in the water,” I said in Spanish to the woman behind the counter of the souvenir shop. Laid out in front of us were more than 50 pieces of jewelry and other products made from the shell of the critically endangered hawksbill.

“No!” was the sharp response, catching our group off-guard.

Of course, we weren’t exactly regular tourists doing souvenir shopping. Our group was made up of myself, the two leaders of Fundacion Tortugas del Mar, and Dan Berman, a donor who supports both of our organizations.

We were visiting Colombia’s Caribbean coast to see first-hand how the Fundacion has been studying and combating the tortoiseshell trade. Cartagena was identified as the second-largest site for the sales of these products in the region in our Endangered Souvenirs report, after Nicaragua. Data collected by Fundacion Tortugas del Mar over a 5 year period showed that on average more than 2,500 products were being sold per year by 19 vendors and shops, with an estimated value of more than $20,000.

The good news is that sales of these products has dropped dramatically. After years of working with local authorities to confiscate these products from vendors, the trade is slowing down. Too Rare To Wear, with the support of the Berman Fund and other donors, is providing funds and resources for Fundacion Tortugas del Mar to train police, do outreach to vendors, souvenir shops, and tourism businesses to wipe out both the supply and demand for these products.

Hawksbill turtles at one time were quite common in tropical areas around the world. Their shells were plastic before plastic was invented and millions of shells were shipped around the world over the past few hundred years; 2 million shells alone were shipped to Japan between 1950 and 1992, when the legal international trade was finally ended. This has had a devastating effect on the hawksbill, it is now considered critically endangered and their numbers have plummeted to now roughly 15,000 adult females on the entire planet.

The first shop that we visited was in Tolu, a coastal town that is a popular spot for Colombians to vacation. The stand was unassuming, without walls on a stretch of dirt off the main road. The turtleshell products were significant though not a large percentage of the total products being sold. The owner quickly figured out that we were not shopping for souvenirs and her demeanor changed from one of friendliness to confrontational. Her family is Wayuu, an indigenous group that views wild animals like sea turtles more as a resource than a tourist attraction or animal to be appreciated for its intrinsic value.

Karla and Cristian are bringing their programs to towns like Tolu and nearby Coveñas and Rincon del Mar. Their first step is to inventory the amount of products being sold, and then reach to the vendors to explain that these sales are illegal and encourage them to sell other products. Finally, the last step is to work with government authorities like the police to visit these shops and confiscate the products. The loss of the money spent on the products is often enough to encourage the vendors to stop selling them, though it can take a few times. If there are repeat offenders, eventually the authorities may impose fines or jail time, but the hope is to stop these sales without resorting to that.

Later that day, we had a meeting with nine souvenir shop owners in Cartagena, in a beautiful location inside the historic walled city called “Las Bovedas.” These shops often sold turtleshell products, primarily to cruise ship passengers, until the Fundacion started to work with police to confiscate the products. Now, none of these shops sell these products and many are enthusiastic in their support to help stop this trade.

Las Bovedas

Meeting with shop owners

These shops are the first in a new program that Too Rare To Wear and the Fundacion are launching called “Turtle-Free Souvenir Shops.” The shops will receive a sticker that shows their participation and we will work with tour operators to bring traveler to support these shops for their participation. We spent an hour discussing the issue with them, answering questions on how they should respond to tourists asking for turtleshell, and how we plan to support their efforts.

Our next stop was Hotel Punta Faro, a luxury resort on Mucura Island, located within the Corales del Rosario y de San Bernardo National Natural Park, that is a big supporter of turtle conservation efforts. The national park, the hotel, and the Sueños de Mar Foundation has a collaborative work agreement that includes environmental education with children, young people, and fisherman of the local community. We were lucky to witness a release of 12 sea turtles that the resort rescued through a program they have where they offer chicken to fishermen who bring them the turtles instead of consuming them. Punta Faro is one of the first hotel partners of Too Rare To Wear and is putting together a display to share with their clients about the turtleshell issue, which will help to reach a key market for these high end products.

Our last stop in Rincon del Mar showed how much work remains. We were there to run a workshop with local teachers and community leaders about sea turtle education, I made a stop to a well-known souvenir shop in town that is a major seller of turtleshell. The owner calls himself the “Rey de Carey” or “King of Hawksbill” for the amount of products he sells. And he definitely sells a lot. In one visit, we counted more than 100 rings, dishware, necklaces, and other products.

The impressive work of Fundacion Tortugas del Mar has made great progress in slowing the turtleshell trade in Colombia. While there remains some trade in Cartagena and surrounding areas, by working closely with the tourism industry and local authorities, Karla and Cristian are providing a model for how to successfully save hawksbill sea turtles.

Natural & Cultural Treasures of Colombia’s Caribbean Coast

Colombia’s Caribbean coast is an intense place. Intense heat, intense rain, and arriving during a World Cup match, intense soccer fans. Making our way from the airport to our hotel in the historic Getsemani neighborhood was easier with many people off the street but the flooding from a brief tropical storm slowed our progress. The rain cooled off the summer heat and we celebrated the victory that evening by visiting the historic walled city, where we took in an beautiful and intense performance of Afro-Caribbean dance.

Cartagena's walled city

We came to this up and coming South American destination to scout for a new trip that we hope to offer in 2019, to see first-hand the great work of our partner Fundacion Tortugas del Mar in addressing the turtleshell trade here, and to train teachers in sea turtle education. We packed in a lot in a short time, but in less than a week, we visited two islands, saw a bunch of turtles (and turtle products for sale), and met some inspiring conservationists, including Karla and Cristian of the Fundacion. I’ve been visiting Colombia since the early 2000’s and seeing how this country is returning to peace after a long civil war is extraordinary and hopeful.

Our first visit was to Isla Fuerte, about a 5 hour drive from Cartagena. This small island is home to a hawksbill nesting beach and is hosting a sea turtle festival in August to celebrate the release of a number of juvenile hawksbills. The hawksbills were saved from a nest that was laid too close to the water and a local resident headstarted the hatchlings to help save them. Our visit coincided with a local holiday and intense music rang across the island through the night.

Upon our return, we headed back to the walled city to meet with souvenir shop owners. Las Bovedas is a series of stalls filled with souvenirs in a historic building that at one point was a major spot for sales of products made from turtleshell. Over years of working with local authorities to confiscate the products, the folks from Fundacion Tortugas del Mar have significantly reduced the number of these products being sold around the city. Many of these shop owners are now enthusiastic about helping to protect turtles, making Las Bovedas the ideal spot to launch our new Turtle Safe Souvenir Shop program in partnership with the Fundacion, part of our Too Rare To Wear campaign. Travelers to Cartagena can look for this seal to know that they support shops who help protect sea turtles (and soon elsewhere around the region.)

Las Bovedas Souvenir Shops

From there, our next stop was Mucura Island, a beautiful tropical isla in the San Bernardo Archipelago. After relaxing two-hour boat ride through the islands, we arrived to Punta Faro, a spectacular four-star resort that has strong ties to the local community and strong efforts to protect sea turtles. The highlight of our visit to Colombia was a program working with a group of local students who have a very active environmental club. After playing games with the kids, we headed back to the resort so the group could help release a bunch of sea turtles to the ocean. Punta Faro has a wonderful program where fishermen who catch turtles while fishing can bring them to the resort, where they exchange them for chicken (instead of eating them).

In all, eleven turtles were released in front of an enthusiastic audience of resort guests and local kids, one very large loggerhead, 4 hawksbills, and 6 green turtles. This program is helping save turtles from poaching, providing food for local fishermen, educating both kids and tourists, and providing important information on local turtle populations. In addition, Punta Faro is an enthusiastic support of Too Rare To Wear and is the first hotel to share our materials with their guests, who are a key market for turtleshell products.

While there, we explored the waters around the island, looking for turtles and checking out the coral reefs and fish. We also passed by Islote Santa Cruz, known as the one of most densely populated island in the world, with 400 people living on just about one hectare. That night after dinner, we took a short boat ride the swim in an area with beautiful bioluminescence.

Our final stop on our exploration of Colombia’s coast was Rincon del Mar, a small town on the mainland coast that is a popular spot for local tourists to enjoy the blue Carbibbean waters. Here, we hosted with the Fundacion a workshop for local teachers and leaders, teaching them about sea turtles and educational techniques. Participants included roughly 30 teachers from the surrounding communities, national park staff, local authorities, and residents of Rincon interested in participating in sea turtle conservation. This workshop was the launch of a new effort to build support for efforts to protect sea turtles in the town and address the sale of turtleshell in local shops.

Turtle Education Workshop

Turtleshell and other products for sale in Rincon del Mar

On our last night in Cartagena, we celebrated with a final dinner in a fantastic open-air Italian restaurant in Getsemani. We celebrated the success of efforts to end the sale of turtleshell here, making plans to offer the first ever sea turtle trips to this area, and launching new efforts to help the sea turtles that live along this spectacular stretch of coast.

New Directions for Too Rare To Wear

While traveling in Nicaragua in 2015, our president Brad Nahill went souvenir shopping with his daughter in the coastal town of San Juan del Sur. Avoiding shops and vendors that sold these products was so challenging that we decided to launch Too Rare To Wear, a campaign that would work with the travel industry to try to reduce the demand for these products wherever they are found around the world.

Since our launch in late 2016, Too Rare To Wear has:

· Completed Endangered Souvenirs, the first regional survey of turtleshell sales in Latin America and the Caribbean in more than 15 years. We found more than 200 shops and vendors selling more than 10,000 products in 8 countries. This information is key to identifying the most important places to invest resources, inform enforcement authorities, and establish a baseline to be able to monitor the success of the project;

· Built a coalition of more than 80 conservation and tourism organizations working to end the demand for turtleshell products. The coalition includes more than 40 tourism companies, which include both leading adventure travel operators in the US as well as key local operators in Latin America. The coalition also includes important conservation partners such as the US Wildlife Trafficking Alliance, WildAid, the Humane Society International, and many regional and local organizations;

· Reached millions of people with our undercover video footage. We put together a video on turtleshell products with popular website The Dodo that reached more than 8 million people around the world. We also did a how-to video on recognizing turtleshell with Travel For Wildlife that reached tens of people through social media;

· Created a variety of outreach materials on the turtleshell issue including the first simple guide for recognizing turtleshell, an infographic, and a photo library available for free use for the media and outreach. Our materials have been included in the US Wildlife Trafficking Alliance tourism toolkit, used by major tourism companies and associations including airlines and cruise lines and have been translated into Spanish, German, and French;

· Working with local partners in Nicaragua and Colombia to launch campaigns to work with local officials and tourism businesses to educate travelers about this issue;

· Created a “pledge to avoid turtleshell” which has been signed by more than 6,500 people from roughly 100 countries. These committed people are crucial to expanding the reach of our campaign. We have also built a social media network of about 5,000 people and launched a central website that has had more than 15,000 visitors to date.

We are excited to announce that, with the support of a number of great sponsors including the Bently Foundation, Pacsafe, Lush Cosmetics, the Intrepid Foundation, and others, this year we will be dramatically expanding Too Rare To Wear.

Our plans for the next year include:

Expanding the campaign to Asia, where large shipments of these products have been found in China, Vietnam, Japan, Indonesia, and elsewhere;

Launching a new effort to engage divers and the dive industry on this issue. Few travelers have a bigger stake in healthy coral reefs than divers and these products can be found in most places that have coral reefs around the world;

A new program called "Turtle-Safe Souvenir Shops" that will encourage stores to stop selling these products and give travelers places to look for when traveling to spots where these products are sold;

Working with Fundacion Tortugas del Mar in Colombia to expand their efforts to address this issue in Cartagena and other destinations, including the coastal communities of Tolu and Coveñas;

Bringing together a coalition of conservation groups and tourism companies in Nicaragua to develop a national strategy to reduce the sale of turtleshell products in the country.

A new ad campaign that will help bring awareness to this issue by helping people connect the animal in the water with the products in the store with.

We hope you will join us for this exciting next stage of Too Rare To Wear!

10 Years, $1 million For Conservation & Communities

When we launched SEE Turtles in 2008, we didn't know what kind of impact we could have. Nobody had ever tried to do conservation this way and we heard skepticism that tourism could be a good tool for conservation. Ten years later, we are now an independent non-profit and we have passed a major milestone, $1 million for more than 20 sea turtle conservation and nearby communities across Latin America and the Caribbean!

These funds help small, community-based organizations fund their research and conservation efforts and provide volunteer support. The money spent in communities near sea turtle hotspots can be as effective as money going direct to conservation; the more communities benefit from live sea turtles, the more they support the conservation programs.

Our totals include:

More than 1,200 travelers participate in trips to 8 countries, completing more than 4,000 volunteer shifts;

More than $600,000 generated for conservation programs through direct payments ($130,000), donations ($50,000), grants ($250,000), income for our programs ($130,000), and volunteer support ($40,000);

More than $250,000 spent in local hotels, restaurants, and stores;

Roughly $130,000 in in-kind support including marketing, social media promotion, and other support.

To celebrate this milestone and our anniversary, we are offering a special $100 per person discount on all of our conservation tours and doing a contest giving away 5 turtle gift packs for people who sign up for our monthly enewsletter.

We hope you can join us to help us raise the next million!

-Brad Nahill & Wallace J. Nichols, Co-Founders

2017 SEE Turtles Annual Report

2017 was a great year for both sea turtles and SEE Turtles. Research is showing an improving situation for a number of sea turtle populations around the world and several important nesting beaches had their strongest year on record. SEE Turtles became an independent non-profit, reached the 1 million hatchlings saved milestone, our conservation trips had their biggest impact to date, and our Too Rare To Wear program got off to a great start. And the best is yet to come!

Our decision to become an independent non-profit was a tough one. We had great support from our past fiscal sponsors Oceanic Society and The Ocean Foundation that helped us grow and thrive. Being an independent organization though will allow SEE Turtles to both grow and become more efficient. Our overhead costs will drop, allowing us to invest in growing our programs and saving more turtles over the long-term. We are very thankful to our wonderful new board of directors for and to Oceanic Society and The Ocean Foundation for their help in this transition.

Looking back, 2017 was the year we hit our first major milestone for our Billion Baby Turtles program, one million hatchlings saved. We also raised more than $6,000 to help restore Puerto Rico sea turtle conservation efforts. We’re thrilled to be able to support many important sea turtle nesting conservation programs and look forward to increasing our support for these programs and bringing in new partners.

Our Too Rare To Wear campaign, which started in late 2016, made great progress in elevating the issue of the turtleshell trade in the tourism industry, with more than 80 tour companies and conservation organizations partnering on the campaign, innovate educational tools, a ground-breaking report, and millions of people reached. Our Sea Turtle Conservation Tours had more than 100 travelers participate in trips with roughly 400 volunteer work shifts and more than $100,000 generated for turtle conservation and local communities.

Looking ahead, 2018 promises to be another exciting year. 2018 is our 10th anniversary and hopefully passing $1 million generated for conservation and communities. We are planning a month-long celebration with discounts on tours, giveaways, and much more, be sure to follow us on social media to learn more. We will also be expanding Too Rare To Wear to Asia, offering a great slate of conservation trips, and expanding our support to new nesting beaches through Billion Baby Turtles.

Thank you for joining us for this ride. SEE Turtles would not exist without our wonderful donors, travelers, schools, and partners.

-Brad Nahill, President

One Million+ Hatchlings Saved!

We're reached our first major milestone in our Billion Baby Turtles program! Since our official launch in 2013, we have provided enough funds for our network of turtle conservation partners around Latin America and the Caribbean to save more than 1 million hatchlings (1,230,460 to be exact)!

To celebrate, we are taking this opportunity to raise funds for sea turtle conservation work in Puerto Rico, which was recently devastated by hurricanes. Every donation will be matched and our goal is to raise at least $5,000 to help the Vida Marina project of the University of Puerto Rico rebuild their programs after the storms. We are also holding a month of promotions to celebrate, giving away a gift pack of fun turtle stuff on each of our social media platforms.

A huge thanks to every donor, sponsor, and traveler for helping us reach this goal and our deep appreciation goes to all of our partners who spend countless hours walking dark nesting beaches to save these extraordinary animals. It is our pleasure to be able to support your work!

Billion Baby Turtles Surpasses 1 Million Sea Turtle Hatchlings Saved

Beaverton, OR, Nov. 1, 2017 - Billion Baby Turtles has helped conservation organizations across Latin America save more than 1 million sea turtle hatchlings. Recent research has shown that when sea turtle nesting beaches are protected, endangered populations can recover. Billion Baby Turtles, an initiative of the conservation organization SEE Turtles, brings together sponsors, patrons, schools, and travelers to raise funds that go to helping grassroots organizations that work on important turtle nesting beaches to protect turtles, their eggs, and their hatchlings from poaching.

Since 2013 the initiative has helped save approximately 1.2 million hatchlings by giving more than $200,000 in grants to 17 organizations in 9 Latin American countries. For every dollar donated, 5 hatchlings have been saved and roughly 90 cents of every dollar have gone to conservation efforts. Grants have supported programs restoring five of the seven species of sea turtles found around the world.

“The goal to save a billion baby sea turtles is wildly ambitious, and through the dedicated leadership of SEE Turtles we now know it’s totally within reach,” said David Godfrey, executive director of the Sea Turtle Conservancy. “It’s very exciting to see the campaign surpass a million saved hatchlings. STC is proud to be helping SEE Turtles reach its lofty goal through a nest protection program we’re carrying out in Panama with funding from the Billion Baby Turtles initiative.”

Protecting nests and hatchlings not only helps to bring endangered sea turtle species back from the brink of extinction, it also helps other species by increasing sources of food for birds, fish, crabs, and other animals. In addition, turtle watching has become an important source of income for many coastal communities and observing and participating in saving sea turtles and hatchlings has been shown to have emotional benefits for travelers and local residents alike at turtle nesting beaches.

Billion Baby Turtles has provided nearly 50 grants to date, ranging from $1,000 to $10,000. The initiative prioritizes small, community-based organizations working to protect beaches that have few other sources of funding and focuses on the most endangered populations of sea turtles. The largest numbers of hatchlings protected have been at Colola Beach, Mexico, where researchers from the University of Michoacan have worked for decades to bring the East Pacific green turtle back from near extinction. Our support has helped to save more than 600,000 hatchlings at this beach. Last year the East Pacific green turtle was downlisted, a sign of a positive trend towards recovery.

Funds are raised from a variety of sources including business sponsors, SEE Turtles conservation tours, individual donors, schools, foundations, and sales from the SEE Turtles online store. Sponsors and foundations have provided roughly half of the more than $200,000 raised, while tour income and individual donations have provided 15-20% each. 2017 was the best year yet for the initiative, with more than 400,000 hatchlings protected, an increase of nearly 25 percent from 2016.

Exploring Belize’s Wild Side by Boat, Snorkel, Canoe, & Inner Tube

Manatee!

No sooner had our boat pulled up to the coral reef for our planned marine life survey, than someone had spotted the long rounded shape of the marine mammal passing by our anchored boat. This being my first opportunity to swim with these extraordinary creatures, I quickly slipped into the water while our group was getting geared up with snorkels and fins.

Manatees are often wary, so I tried to not to scare this one off before everyone was able to see it. But after a few minutes, it was clear that this one not only didn’t mind our presence, it seemed quite curious about us. Several times the female manatee (who we nicknamed “Manuela”) would swim directly toward people in our group, passing just a few feet below them before surfacing for air. Manuela stayed with us for around 45 minutes, eventually deciding she had enough and swimming on.

This manatee encounter was just one of the first activities of our weeklong adventure to Belize with Nature’s Path, the largest independent organic breakfast company in the world. SEE Turtles has partnered with their EnviroKidz line of kids cereals since 2008, and this was our second trip with them to explore wildlife conservation programs with winners of their “EnviroTrip” sweepstakes. We had along with us families from the US and Canada who won out of more than 7,000 entries to the contest.

EnviroTrip Winners from the US & Canada

Our group first met up at Sea Sports, a dive shop in Belize City run by Linda and John Searle, who also run EcoMar, a research and conservation organization focused on marine wildlife. After a short boat ride to their research station on St. George’s Caye, our group met up for an orientation and delicious dinner and to sleep after the long flights from North America.

Our first activity was dolphin watching and we were lucky to be joined by marine mammal research Eric Ramos, who has spent years observing bottlenose dolphins and manatees living in the Belize Barrier Reef. The sea was calm as we headed south towards Gallows Point to look for bottlenose dolphins, though we didn’t spot any for a while. Eventually we saw a single dolphin nearby and stopped to watch him as he swam around our boat. Eric put his drone up into the sky to keep track of him and record video while we watched from the boat. On our way back to St. George’s, we came across a group of 4 more dolphins, including one calf, and watched as they fed.

Our special manatee moment came that afternoon, derailing our plans to snorkel the reef until another day. While we hung out with Manuela, a fisherman working with EcoMar caught a loggerhead turtle that was feeding on discarded catch from a fishing boat, so that we could attach a satellite transmitter on her shell to follow where she goes and learn more about the life cycle of these turtles.

Manuel from Nature's Path watching over Hope as her transmitter is attached