Turtle Blog

SEE Turtles Acquires EcoTeach to Bring Conservation Travel to More Schools

January 14, 2026, Portland OR:

Award-winning conservation nonprofit SEE Turtles is acquiring EcoTeach, a student travel company that has brought thousands of students to Costa Rica over the past 30 years. SEE Turtles —one of the first conservation organizations to focus on conservation travel as a strategy to protect endangered sea turtles —will assume management of EcoTeach in January 2027. As part of SEE Turtles' Conservation Travel program, EcoTeach will retain its name and continue its legacy of connecting students with hands-on sea turtle conservation and life-changing experiences.

SEE Turtles President Brad Nahill volunteering at his first turtle project in Costa Rica (second from left).

SEE Turtles and EcoTeach have a long history of collaboration, dating back to 2008 when SEE Turtles first began offering tours to work with sea turtle projects. EcoTeach has been the nonprofit’s local operator in Costa Rica, having run more than 40 trips together, with nearly 500 travelers and generating more than US $250,000 for turtle conservation and coastal communities. EcoTeach has also participated in the nonprofit’s annual School Fundraising Contest and Sustainable Travel Auctions, donating trips to raise funds for conservation.

But the history between SEE Turtles and EcoTeach goes back much further. SEE Turtles president and co-founder Brad Nahill first traveled to Costa Rica through an EcoTeach program to volunteer with a sea turtle conservation project in 1999. Two years later, the company funded the first season of a leatherback nesting program in Playa Negra, Costa Rica, led by Nahill and his former wife. Following that, Nahill helped grow the EcoTeach Foundation—a nonprofit arm created to expand conservation efforts in Costa Rica.

SEE Turtles is a nonprofit that promotes conservation travel across countries including Costa Rica, Mexico, Belize, Panama, Cuba, and Ecuador. It is one of the few travel organizations—nonprofit or otherwise—to offer a transparent pricing model, called Conservation Impact Pricing, which details how each trip financially supports turtle conservation and local communities. To date, SEE Turtles has brought more than 1,700 people to visit sea turtle conservation sites generating an estimated $2 million for conservation and coastal communities. For these efforts, SEE Turtles has been recognized with numerous honors, including the Global Vision Award from Travel + Leisure, the Changemakers Award from the World Travel & Tourism Council, the Sustainable Travel Award from Skal International, and others.

“We are thrilled to be acquiring one of the most conservation-oriented student travel companies in existence,” says Brad Nahill, President and co-founder of SEE Turtles. “Bringing EcoTeach into our organization will allow us to dramatically grow our conservation travel program — generating more income to protect nesting beaches, fight the illegal turtle trade, reduce plastic pollution, and support sea turtle community leaders.”

Volunteers building a turtle hatchery in Playa Negra, Costa Rica. SEE Turtles President Brad Nahill co-ran this project which was funded be EcoTeach.

Since 1994, EcoTeach has brought tens of thousands of students to Costa Rica and other destinations. The company has been the primary supporter of Estacion Las Tortugas, a turtle conservation camp on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast for more than 20 years, bringing thousands of students and travelers to visit and generating hundreds of thousands of dollars in income for the project and community. In addition, the EcoTeach Foundation has also raised thousands annually to support conservation and research at the station, including the creation of a turtle education center on-site.

“We truly do believe that travel can change the world—it’s not just a tag line,” says Deb Smucker, who owns EcoTeach along with Greg Enright. “We are proud of the work we have done over more than 2 decades to engage teachers and students in conservation work, cross-cultural exchange, and supporting students to broaden their horizons.” We have known Brad Nahill longer than we’ve owned EcoTeach. We’ve seen him launch SEE Turtles and grow it in size and impact. His excitement about this next chapter for EcoTeach is contagious and we can’t wait to see where SEE Turtles goes next!”

For more information, contact:

Brad Nahill, SEE Turtles President

brad@seeturtles.org / 800.215.0378

Meet Our Two New Sea Turtle Community Leaders!

Adrian de Jesus de Hoyos, Fundacion Tortugas del Mar (Colombia)

is an environmental leader dedicated to conserving natural resources, with a focus on coastal marine ecosystems and animals. He excels at leading teams, fostering collaboration and mutual respect, and fully committing to projects, ensuring their success and sustainability. His interests include community leadership, mangrove restoration, and turtle release.

Adrian has worked with our partner Fundacion Tortugas del Mar since 2016 where he has coordinated and executed sea turtle release and conservation processes in the San Bernardo Archipelago in the Caribbean. He has also done learning exchanges with local experts on sea turtles of the Colombian Pacific and Caribbean, collected biometric data and tagged sea turtles, and has led awareness and education initiatives on the importance of sea turtles on the islet of San Bernardo. Previously he coordinated field activities of the conservation group Ecosabios in the San Bernardo archipelago and also was a research assistant in Tortuguero, Costa Rica, one of the leading nesting beach research programs in the world.

The San Bernardo Archipelago is the most important feeding ground for hawksbill turtles in the Colombian Caribbean. However, although their consumption has decreased in recent years, it remains a threat to the turtles, as does the sale of their shells for making rooster spurs and hawksbill handicrafts in the mainland municipalities near the archipelago. For this reason, Adrian will conduct turtle monitoring in the area and carry out awareness campaigns with local fishermen and children to promote the conservation of sea turtles, with a focus on the hawksbill turtle.

Fundacion Tortugas del Mar has led efforts to reduce the hawksbill shell trade in Cartagena with incredible results, reducing the sale of these products by an estimated 80%. They have been one of the lead partners of our Too Rare To Wear campaign, where they conduct patrols to find these products, train law enforcement, and work with souvenir shops to prevent their sale.

Learn more:

Wiguidili Crespo, The Leatherback Project (Panama)

Wiguidili is a dedicated marine biologist from the Guna Yala, an Indigenous territory on Panama’s Caribbean coast. She recently completed her bachelor’s degree at the University of Panama and is contributing to sea turtle conservation and community engagement in Guna Yala. Her work includes leading the monitoring, tagging, and environmental education efforts for leatherback turtles at Armila Beach as part of The Leatherback Project's Yaug Galu initiative. Furthermore, she has collaborated with the CONAP Project, supporting research and conservation activities focused on hawksbill and green turtles.

Wiguidili is known for her strong commitment to marine conservation, particularly her community work in Guna Yala, which serves to inspire younger generations to appreciate and protect biodiversity. The Yaug Galu Project is a community-based scientific initiative dedicated to the conservation of the leatherback sea turtle on Armila Beach in the Guna Yala region. It is part of The Leatherback Project and combines the traditional knowledge of the Guna people with scientific research, integrating the active participation of the community in nighttime monitoring, marking and identifying individual turtles, relocating nests, and providing environmental education. This strengthens local capacities for leatherback turtle conservation and ensures that future generations can continue to share the beaches with this species.

The Leatherback Project also partners with Too Rare To Wear to train law enforcement and educate local communities about the illegal trade. Our Billion Baby Turtles program also supports this program with a grant for the first time in 2026.

Learn more:

Meet Our Kenya Guide - Julie Church

For our Kenya Coast & Safari trip, SEE Turtles is working with Seas4Life and Albatros Expeditions and Julie will lead the coastal portion of the trip. She is a visionary force in marine conservation and the founder of Seas4Life, a pioneering organization redefining how we connect with the ocean. Through Seas4Life, she bridges purposeful travel, ocean conservation, and ocean literacy across the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), creating transformative experiences that merge exploration with impact.

With more than 25 years of experience working across Africa, the Western Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea, Julie has become a respected authority in developing regenerative, ocean-centered initiatives that unite conservation and meaningful travel.

Born and raised in Kenya in a family rooted in safari, wildlife conservation, and farming, Julie’s relationship with nature runs deep—woven through generations. Her professional journey has taken her from the coral reefs of East Africa and seagrass meadows of Indonesia to influential advisory roles with organisations such as WWF, IUCN, and the NEPAD Coastal & Marine Secretariat. In these roles, she helped design and implement projects that strengthened marine governance, empowered coastal communities, and advanced sustainable blue economies.

Through Seas4Life, Julie channels her lifelong dedication to the ocean into a movement that invites people of influence to engage with the sea in new, purposeful ways. Each Seas4Life Journey is guided by experts and curated with scientific integrity, offering immersive experiences that support marine restoration, ocean literacy, and sustainable livelihoods. The result: luxury travel with a conscience, where every journey contributes directly to real conservation outcomes.

Meet our Galapagos Guide - Pablo Valladares

SEE Turtles works with Galakiwi, one of the top operators in Ecuador, to offer the Galapagos Turtles and Tortoises trip to this extraordinary destination. Our trips are led by an extraordinary guide with Galakiwi, Pablo Valladares, to ensure that you see and learn as much as you can while on the islands. His combination of deep knowledge and passion for nature will make your visit unforgettable.

After earning his degree in Biology and Natural Sciences from the University of Guayaquil, he traveled to the Galapagos Islands to join a six-month volunteer program with the Charles Darwin Research Station and the Galapagos National Park.

While working with the Giant Tortoise Breeding Center on Isabela Island, his love for conservation and outdoor activities flourished, inspiring him to dedicate the next eight years to a new project. He continued his work with the Charles Darwin Research Station, focusing on education, communication, and community engagement. This experience deepened his connection to the islands, their people, and especially to Isabela Island, where he has made his home since 1998.

In May 2006, Pablo left the research station to become a Naturalist Guide, sharing his knowledge, experiences, and love for nature with visitors from around the world. He continues guiding to this day, still based on Isabela Island. In recognition of his dedication and passion, Pablo was honored in 2018 with the title of “World’s Top Conservation Guide” at the Wanderlust World Guide Awards.

Known for his infectious enthusiasm and easygoing personality, Pablo ensures that every journey is filled with learning, laughter, and unforgettable experiences.

“I believe everyone should love and respect nature—and each other—and work to preserve these beautiful islands in their natural state for future generations. I can’t wait to share more magical moments with you and to pass on my passion and love for this incredible place. Bienvenidos a Galapagos!”

Billion Baby Turtles Partner Profile: RASTOMA: – Turtle Guardians of Central Africa

A regional network of grassroots groups is protecting sea turtles across Central Africa

For generations, sea turtles have returned to the beaches of Central Africa to nest—green turtles (Chelonia mydas), olive ridleys (Lepidochelys olivacea), leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea), and hawksbills (Eretmochelys imbricata). But in recent decades, the turtles now face a myriad of human threats: eggs taken from nests, adults caught for meat, beaches reshaped by construction and industrial fishing lines in the water.

The Network of Actors for the Conservation of Marine Turtles (RASTOMA) in Central Africa is a group of 11 grassroots organizations across Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, São Tomé and Príncipe, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, working to preserve sea turtle populations in their natural habitats over the long term. Each member group works in its own corner of the coast to monitor nests, patrol beaches, work with fishers, and collect data.

Olive ridley hatchlings protected by RASTOMA Network in Democratic Republic of Congo. Credit ©David Mbuli

RASTOMA works in Central Africa because sea turtles don’t stay in one place—they migrate across countries. So, to protect them effectively, conservation efforts need to happen at a regional level. RASTOMA supports local communities to lead conservation efforts and helps create small businesses so people can earn money in ways that don’t harm turtles. The network also helps its member groups share knowledge, build skills, and have a bigger impact—for both sea turtles and the coastal environments they depend on.

And in order to give communities a better understanding of conservation project activities, to gain their support and to propose activities that are profitable and adapted to local contexts, RASTOMA also encourages involving local communities in the design and choice of projects.

The main community approaches carried out by RASTOMA member structures are:

Beach Patrols: More than 50 trained fishers patrol nesting beaches, protect eggs, collect data, and deter illegal hunting.

Port Monitoring: Community members, including women, check landing sites and markets for illegal trade in turtle products.

Responsible Fishing: Around 150 fishers in Cameroon have been trained in sustainable techniques to reduce bycatch and boost incomes.

Ecotourism: More than 25 local residents have become eco-guides, creating income while promoting turtle conservation.

Alternative Livelihoods:

Women in the Iyassa community produce and sell coconut oil.

Fishers in Dizangue have taken up beekeeping.

Smokehouses and snail farms help reduce pressure on mangroves and turtle populations.

Women farmers are growing cassava, plantain, and maize with support from agricultural partners.

Olive ridley turtle returning to the water after nesting. Credit RASTOMA

We’ve provided 9 grants totaling about US $80,000 to RASTOMA over the past three years to help fund their efforts in Cameroon, Gabon, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea including night patrols and beach cleanups. Through this partnership, they’ve helped protect more than 147,000 baby turtles since 2023 and collected more than 7,000 lbs during Sea Turtle Week beach cleanups. These funds have been provided by the J&K Berman Memorial Fund which provide multi-year grants to establish new conservation programs on important nesting beaches.

“Thanks to support from SEE Turtles, we’ve not only seen a significant reduction in poaching rates at our key nesting beaches, but we’ve also been able to strengthen community involvement. Local communities have played an increasingly active role in patrols, nest protection, and awareness campaigns—becoming true allies in the fight to protect these endangered species,” writes RASTOMA.

RASTOMA team from Gabon. Credit: RASTOMA

“This collaboration has laid the foundation for more inclusive and sustainable conservation practices. We look forward to continuing this valuable partnership to ensure the long-term survival of sea turtles and to further empower the communities who share their habitat.”

Learn more:

RASTOMA website (in French)

Billion Baby Turtles passes 20 million baby turtles saved milestone

SEE Turtles’ Billion Baby Turtles Program Surpasses 20 Million Hatchlings Saved

Portland, OR - SEE Turtles, an award-winning nonprofit focused on protecting endangered sea turtles, is proud to announce a major milestone: more than 20 million sea turtle hatchlings have now been saved through its flagship program, Billion Baby Turtles.

Conceived in 2013, by late co-founder Wallace J. Nichols, Ph.D., with the simple question, “How much does it cost to save a hatchling?”, the program has grown from supporting a handful of nesting beaches to becoming one of the largest private funders of sea turtle conservation globally. Today, the program supports more than 3 million hatchlings saved each year through partnerships with over 50 organizations working at more than 60 beaches in 25 countries.

Leatherback hatchling from Panama. Photo Brad Nahill / SEE Turtles

“This milestone is a testament to the power of grassroots conservation,” said Brad Nahill, president of SEE Turtles. “From local community members protecting nests to students raising funds, it’s a global movement to save these marine reptiles—one hatchling at a time.”

Since its inception, Billion Baby Turtles has distributed more than $1.5 million in conservation grants, focusing on the most endangered species and populations, including hawksbills and Eastern Pacific leatherbacks. The program prioritizes projects that engage local communities and address high-impact threats to nesting beaches, like consumption of turtle eggs and meat.

How SEE Turtles Works: A Community-First Approach to Conservation

SEE Turtles’ approach centers on empowering local communities as conservation leaders. Its grantmaking model supports locally-run nesting beach programs, providing critical funding where international support is often limited. By supporting local residents in nest protection—often providing employment opportunities and economic alternatives—Billion Baby Turtles helps shift the narrative from exploitation to stewardship.

The organization also invests in education and sustainable travel to protect turtles and their habitats.

Colola Beach: A Conservation Success Story

One of the program’s most remarkable success stories comes from Colola Beach in Mexico, where the Nahua Indigenous community, in collaboration with the University of Michoacan, has led a dramatic recovery of the black turtle (a sub-population of green turtle).

From fewer than 600 nests in the late 1990s, the beach now sees tens of thousands of nests per season, producing millions of hatchlings—making it the most important black sea turtle nesting sites in the world. SEE Turtles remains the only international donor to this program, having supported this work since 2013.

University of Michoacan researcher Carlos Delgado, Ph.D., who has worked on this beach since the 1990’s, says “This population has reached or surpassed pre-Industrial levels, a unique thing with sea turtles, and an extremely rare victory in conservation of any wildlife worldwide. Funding and volunteer support from SEE Turtles has been critical in maintaining this success.”

Black turtle nesting at Colola Beach. Photo: Juan Ma Contortrix

Looking Ahead: From 20 Million to 50 Million

With threats like climate change, illegal hunting, plastic pollution, and habitat loss still endangering sea turtles worldwide, SEE Turtles aims to expand Billion Baby Turtles’ reach to even more beaches and underfunded regions. The organization is currently launching its 2025 Year-End Campaign, with donations matched up to $5,000 that will go to protect important leatherback nesting beaches in Mexico through Grupo Tortuguero, an organization co-founded by J. Nichols.

“We’re only just beginning,” added Nahill. “We believe 50 million hatchlings saved is within reach—and we invite people everywhere to be a part of that journey.”

To learn more, donate, or get involved, visit:

👉 www.SEETurtles.org/20-million

A Billion Is A Big Number

J. Nichols

J. Nichols was always full of big ideas. Like “lets track a turtle across an ocean when nobody else has.” Or “lets start a project that helps turtle communities benefit from conservation tourism.” Or my favorite, “Lets invite Michele Obama to release hatchlings in Florida.”

But when he came to me in 2013 with an idea to save a billion hatchlings, my first reaction was skepticism. How on earth would we do that??? But as we discussed, I started to come around (as I did on many of these ideas, if not all of them.) When he asked, “How much does it cost to save a baby turtle?”, that got my interest going. “Lets find out!” I said. We reached out to several of our closest partners to ask them and started gathering the data.

The range was wide from those we polled, to a few pennies at places like Colola Mexico, to several dollars each at leatherback nesting beaches in Costa Rica. But when we averaged them out, the answer was surprising, .20 cents each or 5 saved per dollar. Billion Baby Turtles was born.

We began raising funds and giving them to a few groups we knew well from our past work in Mexico and Costa Rica, groups like Latin American Sea Turtles (that I had worked for), the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative, and Paso Pacifico in Nicaragua. Over time, as we brought in new partners, the cost dropped to .10 cents to save a hatchling or 10 for one dollar.

The first few years were modest, raising and distributing between $30,000 and $50,000 to 10-15 groups per year and helping to save a few hundred thousand hatchlings per year. We reached our first million saved by 2017, taking 5 years to reach that milestone. We had a few loyal corporate and foundation sponsors supporting the program those first years, including Nature’s Path Foods, Endangered Species Chocolate, and World Nomads Insurance.

Billion Baby Turtles started picking up steam in 2019 when we first passed $100,000 in grants for the year and saving more than a million in one year alone for the first time and 3 million total. That year was the first year we worked with the Berman Memorial Fund to help launch new nesting beaches. That collaboration has blossomed into becoming one of our biggest supporters and has now provided several hundred thousand in funding for 24 projects around the world.

The program then grew rapidly over the next 3 years, reaching nearly 2 million hatchings and $175,000 in grants by 2021. In 2022, we got our largest corporate donation from Soda Stream of $100,000, helping to save a million hatchlings alone.

Leatherback hatchling. Photo: Neil Ever Osborne

Billion Baby Turtles is now our flagship program, providing more than $250,000 in grants per year to 40 to 50 important nesting beaches. We have averaged between 3 and 6 million hatchlings saved each year since 2022 and expect to grow even more over the next few years. From a couple hundred thousand saved per year, we have now provided more than $1.6 million in 330 grants over the past 13 years, providing resources for community organizations on more than 60 beaches in 25 countries to hire residents to patrol the beaches and release the hatchlings. 23,400,000 baby turtles saved total through 2025.

From taking 5 years to reach our first million, and then 5 million more in 3 years, and then ten in two years, we have now reached more than 20 million baby turtles saved. The only sad part is that we lost J. in 2024, so he is no longer here to enjoy this milestone with us. But we celebrate his memory by raising funds to support beaches through Grupo Tortuguero de las Californias, an organization he co-founded decades ago. As he would surely joke, “Only 880 million hatchlings to go!”

Learn more about this huge milestone and how you can help save baby turtles.

Billion Baby Turtles Partner Profile: Turtle Love

How one small organization is empowering coastal residents to safeguard nesting beaches and build a future rooted in conservation.

Tortuguero National Park on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast is a clear example of what long-term conservation can achieve. After decades of protection, its beaches annually host tens of thousands of nesting green turtles (Chelonia mydas)—the largest populations in the Atlantic.

But take a few steps south, beyond the park’s boundary, and the situation shifts. On Playa Tres—a 5-kilometer stretch of unprotected coastline—turtles still face serious threats. This is where Turtle Love, a small nonprofit, is working hard to close the gap. Their team monitors nests, deters illegal hunting, and builds conservation efforts rooted in the local community. Here, green, leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) turtles come ashore to nest, and they still need protection.

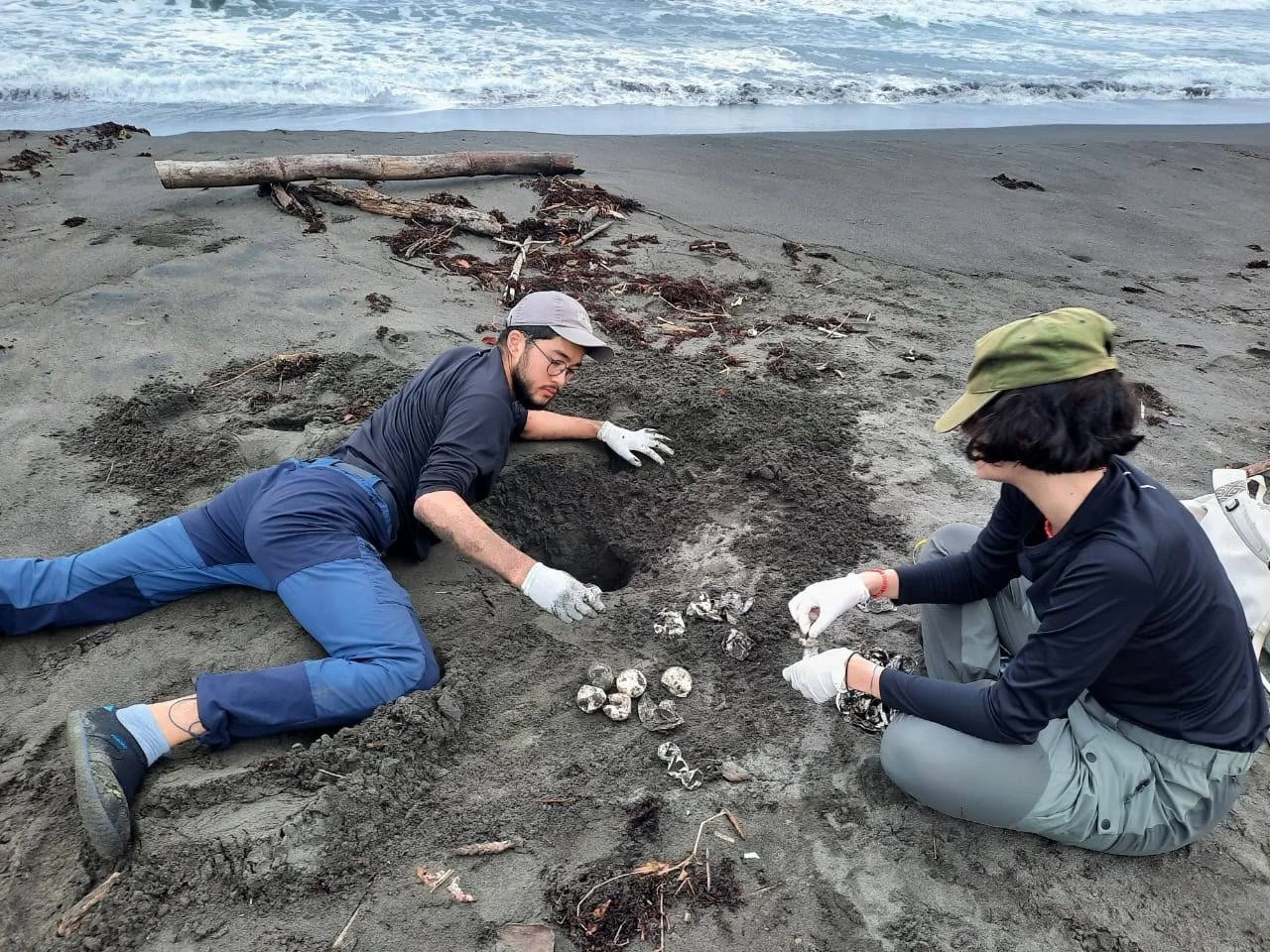

Turtle Love team excavating an old nest in Costa Rica. Credit Turtle Love.

Illegal harvest of nests and adult turtles for meat and shell products is the primary threat Turtle Love addresses. To combat this, the organization monitors nesting activity while actively engaging local communities through education and outreach. They also promote sustainable development by offering alternative livelihoods, such as training and hiring local field assistants and connecting volunteers with host families for homestays.

Their beach monitoring helps reduce hunting in the short term, while involving residents creates long-term change by providing jobs and income that don’t depend on harvesting turtles or their eggs. Most outreach focuses on the small town of Parismina but also reaches Tortuguero and visitors from across Costa Rica and abroad.

Green turtle hatchling. Credit Turtle Love

The science matters, too. In addition to direct protection work, Turtle Love collects and shares critical data with Costa Rica’s Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE). Renato Bruno, a Brazilian biologist and the organization’s president and scientific director who has been working to conserve sea turtles since 2009 leads their scientific team. They monitor nesting activity and poaching trends, providing data that helps inform beach management and national conservation strategies.

At SEE Turtles, we support local groups like Turtle Love because they do the real work—on the ground, in the community, with the animals. They know this stretch of coast. They know the challenges. And they’re not just passing through.

Turtle Love’s Emma Bello, recipient of our Sea Turtle Community Leaders scholarship. Credit Turtle Love

Billion Baby Turtles has provided 11 grants to Turtle Love over the past 7 years to help fund their efforts — whether that’s night patrols, school visits, beach cleanups, scholarships, or data collection. Through this partnership, they’ve helped protect more than 500,000 baby turtles since 2019, and their work continues to make a direct impact for some of the most threatened species in the region. Our Sea Turtle Community Leaders program also supports aspiring biologist Emma Bello with his college studies to become a biologist. In addition, SEE Turtles will be offering a sea turtle conservation trip in 2026 to volunteer with Turtle Love’s nesting beach program.

Learn more:

Billion Baby Turtles Passes 20 Million Baby Turtles Saved Milestone

Billion Baby Turtle Partner Profile: Colola Beach, Mexico

How Native community and a Mexican university are bringing a population back from the brink

When we think of sea turtle conservation, stories of loss often take center stage—declining populations, disappearing habitats, and rising threats. But on the remote beaches of Western Mexico, one turtle’s story is different. Thanks to decades of work by scientists, Indigenous communities, and international partners, the black sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii) has made a remarkable comeback.

This effort is led by the Nahua Indigenous community with support from the Black Turtle Recovery Program at the University of Michoacán Mexico, under the leadership of biologist Carlos Delgado Trejo. It is considered one of the most successful sea turtle conservation projects in the world.

Black turtle hatchling at Colola. Photos by Juan Ma Contortrix

Black turtle returning to the water.

The waters surrounding the Baja California peninsula, including the Gulf of California, are Mexico’s most important fishing grounds. They are also critical habitat for five species of sea turtles classified as endangered or threatened: black, loggerhead, hawksbill, olive ridley, and leatherback. Among them, the black turtle, known locally as tortuga prieta, is the most common. Historically, it has been one of the region’s most important native animals, playing a key role in the local ecology, culture, and economy.

Once considered nearly extinct, the black turtle is a subpopuulation of the green turtle, found only in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. In the 1960s and 70s, these turtles were harvested by the tens of thousands along the coast of Mexico—mostly for their meat and eggs. At the height of exploitation, an estimated 70,000 eggs were taken per night during peak nesting. Nesting female numbers crashed from 25,000 to fewer than 200 by the late 1980s.

Something had to change. And it did.

Young Nahua turtle protectors. Photo by Juan Ma Contortrix.

In 1982, a coalition formed between the University of Michoacán, the Nahua Indigenous communities of Maruata and Colola, and both national and international partners. Their goal: restore the black turtle population along this critical stretch of coastline.

University biologists and the Nahua community began nighttime beach patrols, paying local children to collect eggs and bring them them to protected hatcheries. Once hatched, the young turtles were released into the ocean. urtles had long been a food source and source of income for this community. Now those kids are the local leaders of the program including Angelo Oliveros Ramirez, Russell Leiva, Hector Diaz Orcino, Jose Luis Leiva Valencia, and others.

To make conservation sustainable, the program promots alternative livelihoods—like iguana farming, home gardens, and turtle-based ecotourism. This shift helped communities earn income by protecting turtles rather than harvesting them. The model was simple but powerful: living turtles are worth more than dead ones.

Today, the black turtle is thriving at Colola. In recent years, nesting numbers have averaged more than 30,000 nests per season, with more than 10,000 estimated nesting females—up from just a few hundred in the 1980s. The population is now considered one of the 12 healthiest sea turtle populations in the world.

For instance, in the 2024-25 nesting season, close to 350,000 black turtle eggs were protected in Colola hatcheries, according to a report by Delgado Trejo. It is estimated that a total of 2,627,140 sea turtle hatchlings were released during this season.

Dr. Carlos Delgado of the University of Michoacan with SEE Turtles President Brad Nahill. Photo: Juan Ma Contortrix.

Delgado Trejo continues his research at the university, focusing on the biology and ecology of sea turtles. A major goal of this work has been to better understand the long-distance seasonal migrations these reptiles make between feeding grounds and nesting beaches. Tracking the timing and routes of these movements is key to understanding more about their reproductive and identifying the conservation measures needed to protect them.

SEE Turtles has played a part in that success by funding the nesting beach work, as part of our Billion Baby Turtles program. The funds go towards paying local residents to patrol important turtle nesting beaches, protecting turtles that come up to nest. In 2013, the first year we worked with Colola, we gave the project a $3,000 grant, which helped save 40,000 hatchlings. To date, SEE Turtles has provided a total of 13 grants totaling US $100,000 in funding which has helped to save more than 14 million hatchlings at this important beach!

SEE Turtles also brings travelers to visit this extraordinary beach through our Sea Turtle Conservation Tours. Our Colola trip has brought 4 groups since 2019 to participate in this work. To date, we have brought 47 people and generated more that US $50,000 in benefits, including $28,000 raised for turtle conservation and $22,000 spent in the local community.

Learn more:

Billion Baby Turtles passes 20 million baby turtles saved milestone

Photo: Juan Ma Contortrix.

Photo: Brad Nahill / SEE Turtles

Meet The Plastic Pollution Innovators Helping Our Sea Turtles & Plastic Program

Our Sea Turtles & Plastic program has completed four years of funding efforts to remove plastic waste from sea turtle habitats and support community recycling efforts. Over those years, we’ve provided more than 60 grants to dozens of organization in more than 20 countries. These efforts are working, more than half a million pounds have been collected from nesting beaches and feeding grounds, with more than 40,000 lbs of plastic collected. These grants have supported more than 600 local residents and generated more than $10,000 in benefits to conservation and coastal communities.

As we enter our next phase of this program, we brought on leaders in this field to advise us on how to improve outcomes from these programs and support more of these programs.

Our new advisors are:

Sabine Berendse: Green Phenix (Curacao). Green Phenix is social enterprise driving sustainable development by catalyzing circular and inclusive economies.

Steve Trott: EcoWorld Recycling (Kenya) - EcoWorld’s mission is to formalize a waste collector sector of women and youth to power the plastics circular economy at the Kenya coast, bringing social, economic and environmental benefits.

Laura Exley: Tortugas de Osa (Costa Rica) - Tortugas de Osa has developed a local recycling program that works with the local community to provide income and reduce pollution in an important turtle habitat. They are also now working with the local municipality to explore options to improve recycling efforts.

Dr. Christine Figgener: COASTS (Costa Rica) - Chris has become a leading advocate in the effort to reduce ocean plastic since her viral video of the turtle with a straw coming out of its nose. COASTS works on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast to protect nesting hawksbill and leatherback turtles.

Daniel Quilter: Fuze EcoTeer (Malaysia) - Fuze is an accredited social enterprise that focuses on conservation and community projects including community recycling programs and turtle research.

Green Phenix’s Recycling Center in Curacao

Beach cleanup by COASTS in Costa Rica

We’re excited to implement advice from these incredible folks including offering more multi-year grants, exploring more ways to support our partners in developing markets for their products, improving our grant process, and connecting our partners together to scale up their impact.

In addition, we are supporting the efforts of these advisors with grants to support their work including:

Tortugas de Osa: We are supporting the purchase of a new solar inverter to help power their recycling machines and to purchase an injection mold to diversify their recycled product production. In addition, they will run a coordinated community beach cleanup.

EcoWorld: This donation will support the construction of an ocean plastics and fishing gear collection center in the Watamu Marine Reserve in Kenya. The centre will act as a collection point for local community beach cleaners and fisher groups to bring plastic and gears in return for payment per kilogram from EcoWorld Recycling.

Fuze EcoTeer: This grant will be used to buy a new mould for our precious plastic machine which we will use to make letters so we can make personalised recycled plastic jewelery. Fuze will also organise a clean up in the mangrove areas on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia at the mouth of the Klang river which is one of the top 3 contributors to the ocean plastic problems in Southeast Asia.

Green Phenix: SEE Turtles and Green Phenix are exploring a unique collaboration that blends education, conservation, and circular design: a souvenir series featuring four iconic sea turtle species: Leatherback, Loggerhead, Hawksbill, and Green Turtle.

Reducing Plastic Waste in Cape Verde & Ivory Coast

SEE Turtles, with the support of the Change Happens Foundation, supported the launch of two projects working to reduce plastic waste in sea turtle habitats and develop recycling infrastructure that benefit coastal communities. Through our Sea Turtles & Plastic program, SEE Turtles provided two $5,000 grants to Conservation des Especes Marines (Ivory Coast) and Fundacao Tartaruga (Cape Verde) that are helping to clean up thousands of pounds of plastic from important sea turtle habitats.

Over the grant period, the two organizations achieved significant progress in reducing plastic in these key sea turtle habitats including:

An estimated 96,000 lbs of waste collected between the two sites (11,000 lbs in Ivory Coast and 85,000 lbs in Cape Verde).

44 local residents and a total of 300+ including families benefitting from recycling programs (250+ people in Ivory Coast and 50+ beneficiaries in Cape Verde).

Launch of a recycling center in Cape Verde that provides income for turtle rangers out of nesting season.

Both projects combined generated more than $11,000 in financial benefits for local residents.

Fundacao Tartaruga: Cabo Verde

The Fundacao Tartaruga team, with support from our Sea Turtles & Plastic campaign and other funders, over the past two years have organized 34 beach cleanups, with an estimated 84,000 lbs of plastic collected with the help of 671 participants. These cleanups helped to maintain more than 6 miles of one of the world’s most important nesting beaches for loggerhead sea turtles. Most of the collected debris was transported to the local landfill as there are no commercial recycling facilities available to recycle the majority of what was collected. A small portion of the waste was taken to the LixoLimpo workshop, the small-scale upcycling facililty created with support from these funds by Fundacao Tartaruga.

Over the two years, the foundation has made significant progress in creating infrastructure for upcycling in the country. The process to purchase and ship the equipment took longer than initially anticipated but the workshop is now up and running and being manned by 7 local turtle rangers, allowing them to earn income outside of the nesting season where their salaries are paid. To date, approximately 1,000 upcycled products have been produced, including keychains, flower pots, combs, and other products. They are now also hiring an additional two female residents to produce items for the shop throughout the year. The project has generated roughly US $8,700 from product sales to date.

Beach cleanup, photos: Fundacao Tartaruga

Recycling machine

Conservation des Espèces Marines: Ivory Coast

During the grant period, the Conservation des Especes Marines (CEM) team has worked diligently to reduce plastic waste in the environment through various beach clean-up events. Over the project duration, CEM successfully collected a total of 5,035 kilograms (11,077 lbs) of plastic waste. This amount exceeds the 6,000 lbs Conservation des Especes Marines estimated for the initial application. Most of that amount was recycled through IPC Green Blocks, for a total of 4,835 kg (10,637 lbs), which IPC converts this waste into recycled plastic waste that is used to construct local schools and health centers. This recycled plastic generated $1,800 in income for the community members who participated in the project, in addition to the $1,200 in stipends, for a total community income of about US $3,000.

A total of 35 local people benefited from their involvement in the beach cleaning activities being paid a stipend to participate. This group included 5 people from the local Dawa communities and 5 fishermen, mainly chief fishermen. Each person has an average family of 8 on average, bringing the total beneficiaries to 250+ people. The chief fishermen played a crucial role not only in the clean-up activities, but also in raising awareness among their peers about the importance of plastic prevention. They participated in various clean-up activities, removing plastic waste from key areas such as fishing harbours and important nesting sites within the Marine Protected Area (MPA) beaches. Their involvement has been instrumental in maintaining the cleanliness of these vital ecosystems and promoting sustainable practices within the community.

To encourage the participation and support their income, the project provided financial incentives to cleanup participants of $200 per person total for the four cleanup activities. While the primary motivation was to sensitize and involve them in conservation activities, the financial support served as encouragement and recognition of their contributions. Although this support was not substantial enough to stabilize their economic situation, it demonstrated appreciation for their efforts and helped to foster a sense of community responsibility for environmental conservation.

Ivory Coast beach cleanups, photos: Conservation des Especes Marines

Cuba Nature & Culture Trip Diary

There’s a turtle! Wait, there are two turtles. Three turtles? Yes, three. No there’s a fourth! Wait, hold on, is that a fifth coming out? Yes, there’s another.

I arrived to a Cuba significantly different than the one I last visited in 2016. In some ways, things have advance, wifi is much more common in the cities. And the very confusing two currency system has been done away with. But as many Cubans mentioned, the situation on the island in many ways has become more challenging for the people. Inflation and economic sanctions have taken a toll, causing dramatic emigration and significantly reducing the tourism economy. Blackouts and food shortages have become common around the country. US policy towards Cuba is a major reason for these problems, our continued sanctions and policies toward the country are inhumane and are hurting the Cuban people. Our visit was an opportunity to provide some support for Cubans and their work to protect wildlife.

Square in Old Havana

Statue in Plaza Vieja, Havana

SEE Turtles led our first Cuba Sea Turtle Adventure trip to the island since 2018, under a license with the category of “Support For The Cuban People,” one of the few permissible ways to take Americans to the country. Over a week, we visited different communities and explored some of the most fascinating parts of this endlessly fascinating place. We started in Havana meeting our local guide from Cuban Adventures, Yasiel, one of the most enthusiastic and engaging folks to lead our conservation trips. That was followed by a wonderful dinner at Bazar El Luvre with many local dishes. The next morning, he took us on a walking tour of Old Havana to learn about the history and current situation for the people here. From there, we boarded a bus to head west to beautiful Viñales, a gorgeous unique valley with farmland interspersed with large hills called mogotes.

After checking into a homestay with a lovely family, we had dinner at Finca El Paraiso, an award-winning farm to table restaurant with an extraordinary view. Most of the food is grown on the farm including a delicious medicinal cocktail. Afterwards, we visited a local bar for some fun salsa music and dancing and then headed back to our casas for rest.

View of Viñales from Finca El Paraiso

On Monday, after breakfast with our host families, we visited a local farm to learn how this region was the best place to grow cigars in the world. We also tried some locally made rum and honey and the family served as a delicious local meal. We then made the trek to the island’s furthest western point, Guanahacabibes National Park. We had time for a quick dip in the ocean right in front of our cabins and then showered before dinner with our hosts.

After dinner, biologist Dr. Julia Azanza gave us a wonderful presentation about the decades-long work on the nesting beaches of the park. Here, green and loggerhead turtles nest for several months a year, a project that our Billion Baby Turtles program has supported for the past 10 years. We next hopped on our bus for the drive to the nesting beach, passing through a short bit of forest before arriving to the camp of local volunteers. Before the turtles arrived, I gathered the group and researchers and told them about our late co-founder Dr. Wallace J. Nichols, who was a leading turtle researcher and author of the bestselling book Blue Mind. I brought a bit of J’s ashes along to spread on the nesting beach, a place where he spent much time around the world during his fruitful life.

We watched the clouds pass over and the moon rise as we sat on the beach waiting for the volunteer patrol to finish walking the beach. As we were about to head out, a green turtle came in to nest. We waited patiently for her to find her spot to nest and dig out her body pit. Once she started laying eggs, we approached quietly from behind to observe.

Green turtle nesting at Guanahacabibes

Cabins at La Bajada

She was a pretty big one, measuring more than 3 feet in length and laying more than 100 eggs. This specific turtle had strange patches on her shell, flaking off in an oval shape on some of the scutes, something Dr. Azanza had never before seen. We stayed until she began to camouflage the nest, which turtles do to hide the location and then headed back to our cabins for some sleep after the long day.

The next day, I went with a couple of our other travelers with a local guide to explore the coral reef in Guanahacabibes National Park. We discussed the notable absence of fish, the coral bleaching, and other environmental issues that this park and the ocean in general are facing. That night, we again visited the beach and it wasn’t long before the beach got very busy. One after the other, five green turtles emerged from the water in a short area. This time our group got the opportunity to participate hands on with the students, helping to measure the turtles and count the eggs as they dropped.

Turtle returning to the water, photo Rachel Gamber

As we were wrapping up that work, two students returned from walking the beach and said they saw tracks of hatchlings heading to the water, which meant a nest had hatched that they were not expecting. The group moved quickly to find the researchers and Dr. Julia was digging up the nest to see if any remained. Unfortunately we missed them as all of the eggs had already hatched and walked to the water (which is a rare thing). I walked to the edge of the water to make sure none had been caught in debris and while I was separated from the group, I saw many people start hurrying back towards the camp. There we found the researchers with 25 newly hatched baby turtles, collecting data on each of them. One interesting thing they are finding on this beach is that some of the scutes on the hatchlings were abnormally shaped, with more scutes on one side than the other. Hatchlings shells are normally symmetrical so this is a new and potentially scary development.

On Wednesday, we rested from the long night, sleeping in as we got back to our cabins around 2 am. After breakfast in our cabins, we met a local guide to learn more about the birds of Cuba, including the world’s smallest bird, the bee hummingbird, as well as the national bird, the Cuban Trogon, and got to see one in the wild. That was followed by another snorkeling excursion with our local guide in front of our cabins. We also visited a beautiful viewpoint of this unique stretch of coast.

Cuban trogon

Dinner with our hosts was followed by one of the most fun experiences I’ve had while traveling. Our host Yusniel broke out a guitar and started playing traditional and popular songs for us to sing a long with. The family and neighbors came over to play games including dominoes, a local staple, along with games that our group brought like Uno. We hung out and sang and danced and played deep into the evening.

The next day, we boarded our bus for the ride back to Viñales. Once we arrived, we had lunch at a fun local Cuban-Italian restaurant and then headed to take a horseback riding trip through the valley with local guides to learn about the history, culture, and nature of the area. We discussed what crops people grow to survive and what life on a typical farm is like. We also visited a handicraft market from local artisans which had some very beautiful examples of woodwork, jewelry, etc. Unfortunately many of the tables we saw were selling illegal tortoiseshell, made from the shell of critically endangered hawksbill turtles.

On Friday, we hopped on our bus after breakfast with our local hosts and headed back to Havana, about a four hour drive due to the poor roads. After a bit of downtime at our hotel to rest up, we ate at a private restaurant near our hotel. In the evening, we visited a really unique thing in Havana, the Cuban Art Factory. Once a building where cooking oil was made, it was converted by artists to a night club and art museum at once. We at ate Cocinero with a friend who works with sea turtles which overlooked the factory, a really fabulous meal of local dishes. Then we met some of the rest of the group and wandered the factory. I met a local photographer representing a group whose work was being displayed. I purchased a couple of very beautiful photos from them. A local dancer was teaching some steps, followed by an amazing group called the Rumba Allstars, who played incredible Afro-Cuban music accompanied by beautiful traditional dancers.

Rumba All Stars at the Fabrica de Arte

One of our group dancing with a dancer at Buena Vista Social Club

Our final day we had breakfast and did a drove around the city, talking to local guides about the history of American and Cuban relations and politics. We also visited local art galleries and had lunch in another nearby restaurant called Donde Lis, a leader in her community who during the pandemic helped to feed many residents who had little opportunity for food from the government. Our final cultural activity was visiting the historic Buena Vista Social Club. There, we saw many great artists and dancers and different styles of local music. The dancers brought people up onto the stage and taught some steps and was great at involving the audience.

This was truly one of the best trips I’ve ever taken. So many unique experiences and great people. Hopefully our visit was able to help some of the people here who are struggling from the food shortages, electricity blackouts, and challenges with both the US and Cuban governments.

July Billion Baby Turtles Update

It’s been a busy time! This trimester we have given a total of US $67,000 in 17 grants, with 4 new partners.

With a total of US $90,000 so far, our grants for this first half of the year expect to help around 336,343 baby turtles to get to the ocean. Here are the grants we have provided over the past three months.

Yayasan Penyu Laut Indonesia /Indonesia Sea Turtle Foundation, Pesemut Island, Indonesia

Since 1999 ISTF has done nesting beach conservation and eggs protection for critically endangered hawksbills as well as green turtles at Presemut Island in Indonesia. Most of the work is focused on preventing illegal nest collection and predation. Last season YPLI were able to protect 838 nests of hawksbill and 716 of green turtles. This year Billion Baby Turtles is supporting this project with US$ 4,000 and expects to help more than 57,000 baby hawksbill and green turtles to get into the ocean.

Sea Turtle Conservancy

Bastimentos National Park, Panama

After more than 20 years of sea turtle research in Bocas del Toro Province, Drs. Anne and Peter Meylan formed a partnership with STC in 2003 to monitor increasing nesting hawksbills along the Bocas coast (covering ~50 km of beach in recent years). The area of concentrated work by the Meylans has been three important nesting beaches: Small Zapatilla Cay, Big Zapatilla Cay (both since 2003), and Playa Larga (since 2006), all of which lie completely within the boundaries of the Bastimentos Island National Marine Park (BINMP). Nighttime patrols are also carried out to intercept and tag nesting females on these beaches. Both activities are conducted by beach monitors hired from local native communities with help during most years from international student volunteers; all are trained by the PI’s or by experienced field coordinators. In the last 8 years and thanks to the protection of the area, the number of nests have been increasing from 688 in 2014 to more than 1,200 last season. With US $5,000, Billion Baby Turtles supported the protection of more than 16,000 baby hawksbills.

Soropta Beach, Panama

This project is to address on-going threats facing the leatherback population at Soropta Beach, Panama, while carrying out an in-situ research and recovery program. The 14-km Beach hosts between 200 – 1,200 leatherback nests per year, making it one of the most densely nested beaches for this species in the region. Unfortunately, illegal hunting of leatherback nests remains an issue at Soropta, due to its isolated location, relative ease of access and cultural tradition of sea turtle egg and meat consumption in the area. STC is implementing a two-pronged approach to curtail illegal egg taking: implementing a hatchery and directly housing law enforcement personnel at STC’s Biological Research Station. For this season Billion Baby Turtles support this project with US $4,000 helping to get into the big blue at least 1,600 baby leatherbacks. Plus supplementary income with one of our conservation trips to this station.

Leatherback turtle at Soropta Beach, credit SEE Turtles

Ocean Foundation: Guanahacabibes National Park

Eight beaches are patrolled during the nesting and hatchling seasons (May to October) in Guanahacabibes Peninsula. As for green turtle nesting population, it is the second largest of the archipelago and also exhibits high levels of hatching success. Billion Baby Turtles support this organization with US $4,000 for this season, helping approximately 7,000 baby turtles to get to the big blue.

Everlasting Nature, Kimar Island, Indonesia

This organization in Kimar Island,Indonesia, helps protect hawksbill turtles and the recovery of this population. This island used to have a big problem with illegal taking of nests, this is the main reason for the establishment of this project. Everlasting Nature hires local people as “eggs guardians”, walking the beach every morning and collecting nesting data. They conduct this this project with Indonesia Sea Turtle Research Foundation (Yayasan Penyu Laut Indonesia/ YPLI) as partner. This is a very important area for the endangered hawksbill turtles, they protect around 700 nests per season. They also have few green turtle nests on this island. Our Billion Baby Turtle program supported them with US$ 5,000 for this season and hope they can protect more than 35,000 baby turtles.

ProNatura Yucatán, Mexico

ProNatura Yucatan safeguards 3 of the Yucatan Peninsula's most vital nesting beaches, including Celestun and Holbox, which are key hawksbill nesting sites. The field season spans from early April to late October, during which the team surveys 79 km nightly to document female turtles and nests. They also conduct educational visits to local schools. Last season, the 3 beaches saw a total of 3,229 hawksbill nests, 4,331 green turtle nests, and 5 leatherback nests. Due to loss of US government financial support, we were able to get US $10,000 extra in funding this season. The Billion Baby Turtles initiative aims to support over 33,000 more hatchlings reaching the ocean.

Hawksbill turtle nesting at El Cuyo

Latin America Sea Turtles (LAST): Cahuita & Moin Beaches, Costa Rica

Pacuare North

The Caribbean shoreline is also one of the most important nesting locations for leatherback and green turtles. The beach of Pacuare north, counts between 300-500 leatherback nests and 100-150 green turtle nests in a regular season. Local protection in Pacuare is crucial and also benefits sea turtle conservation programs in neighboring countries as it aims at the same turtle population. Pacuare beach also registers between 5-15 nests each season of the critically endangered hawksbill turtle. Without any protection efforts whatsoever, many nests and even adult turtles would be lost for illegal practices that are still common in this area. Billion Baby Turtles supported this project with US $4,000 and hope to help at more than 700 baby turtles to get to the ocean

Cahuita

Since 2000 ANAI and LAST nonprofit organizations have worked for the protection and conservation of nesting hawksbill and green females and baby sea turtles in Cahuita Beach. During the last decade it was estimated that 90% of the nests at this beach were lost by wildlife predation, illegal egg collectors, or washed out by the ocean. Cahuita’s nest population represents one of the highest numbers reported for Caribbean hawksbill turtles in Costa Rica. For this season, through our Billion Baby Turtles program supported this project with US$ 3,500 to help more than 3,500 baby turtles.

Ecosystem Impact, Bangkaru Island, Indonesia

This non-profit organization works in Bankaru Islands protecting especially green turtles and sporadic nesting leatherbacks. In addition to the protection of nesting turtles, Ecosystem Impact develops law enforcement capacity, campaign and advocacy work, community awareness, rangers training and social media education, all of these programs have as a goal the increase of global awareness of the conservation of marine turtles and other wild species included in the Bangkaru Project. They work with community rangers and campaigns in all the local communities surrounding the project. With US$ 5,000 our Billion Baby Turtles program supported Ecosystem Impact for this upcoming season, expecting to protect more than 5,600 baby turtles to get to the ocean.

Researchers measuring a leatherback turtle. Photo: Ecosystem Bumi

Ayotlcalli, Ixtapa, Mexico

Campamento Tortuguero Ayotlcalli was founded in September of 2011 with the purpose of protecting and help increase the population of three species of marine turtles that nest within 15 kilometers of beaches that include Playa Blanca, Playa Larga and Barra de Potosi in Zihuatanejo. This year, this program won the Grassroot award during the 42 International Sea Turtle Symposium!! Congratulations to Damari and all her team for the great work they are doing! Billion Baby Turtles supported Ayotlcalli with US$ 2,500, helping to protect the 3 different species that nest on these beaches (olive ridleys, leatherbacks and black turtles) and more than 8,000 baby turtles.

SOS Nicaragua, Los Brasiles, Nicaragua 2,000

Since 2019, Sos Nicaragua has been independently implementing conservation efforts on the island of Los Brasiles, starting a permanent sea turtle protection programme that extends to all recorded nesting species. They have developed a conservation model in harmony with turtle egg harvesters, raising local awareness, protecting critical sea turtle habitats and generating new sources of financial sustainability for local families in long-term project goals. The average number of nests protected annually usually exceeds 100, mostly nests of ridley turtles. Billion Baby Turtles has been supporting this project since 2017, this year with US $2,000 we hope to help almost 2,000 baby turtles.

New Billion Baby Turtles Partners

Bahari Hai, Watamu, Kenya

The 5km Watamu Marine Protected Area beach has had long-term, intensive monitoring & protection as an index nesting beach. However, outside of this Marine Park there has been significantly illegally taken and increased threats to nesting sea turtles. These unprotected sites have great potential. The team have identified 7 nesting beaches over a 30km area that want to validate for longer-term nest monitoring & protection. With US $2,000 we supported Bahari Hai to explore those understudied beaches along with an additional $1,000 donation through our upcoming Kenya Coast & Safari trip.

Green turtle nesting at Watamu Beach. Photo: Bahari Hai

The Leatherback Project, Guna Yala, Panama

The Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) Nesting Ecology Project at Armila Beach, Guna Yala, Panama, focuses on the study and conservation of this vulnerable species. This project addresses two significant threats impacting the nesting ecology of the leatherback sea turtle at Armila Beach: coastal erosion and plastic debris pollution. Coastal erosion caused by natural processes reduces suitable nesting areas, jeopardizing hatchling survival. Plastic pollution poses a serious threat to the health of the turtles and their environment. Addressing these threats is important to ensure the conservation of this species. With US $3,000 we expect to help to protect more than 3,000 baby leatherbacks.

Costa Rican Alliance for Sea Turtle Conservation & Science, Playa Gandoca, Costa Rica

COASTS is on a mission to prevent the extinction of sea turtles and protect their natural habitat through scientific research, data-driven conservation actions, habitat restoration, and environmental education. This is a passionate and dedicated team of local assistants, scientists, students, conservationists, citizen scientists, and volunteers. From March until October, this project conducts nightly beach patrols to encounter nesting females (primarily leatherbacks and hawksbill). From November until January, they conduct morning surveys to take care of the remaining incubating nests and to continue to do nest inventories, once they hatch. The goal is to monitor the three nesting populations long-term and to protect the females and their eggs from illegal harvest and beach erosion. We supported this project for the first year with US $3,000 for this upcoming season.

Salvemos Isla Ixtapa, Isla Carey, Guerrero, Mexico

This project started in 2011 and its mission is to protect and conserve sea turtle nests, primarily hawksbill turtles, as it is currently the most important nesting site in the Mexican Pacific. They also conduct environmental education talks and workshops for the general public and schools that visit us on the island. With US $1,000 we hope to help more than 3,000 baby hawksbills to get to the ocean.

Barreros de San Luis, Guerrero, Mexico

Our new partner: Barreros de San Luis, located in the municipality of Técpan de Galeana in the state of Guerrero, Mexico, is made up of more than 40 local people who support the protection and conservation of sea turtles. They protect the critically endangered pacific leatherback, and also the vulnerable green (locally known as black turtle) and olive ridley sea turtles. The main threat in this area is illegal hunting of eggs and adult turtles. For almost 10 years they have protected 90% of leatherback turtle nests in their hatchery and the rest are protected both: in situ and in the hatchery. With the efforts of all collaborators and with good management practices, more than 80% of hatching success in the 3 species has been achieved. They may protect up to 3,500 nests of olive ridleys, 150 nests of leatherbacks and 50 nests of black turtles. With US $5,000, we expect to help them protect around 62,500 baby turtles.

Los Quelonios, Guerrero, Mexico

Another new partner this month, is Chelonios, located in the town of Playa Ventura in the municipality of Copala, Guerrero, Mexico, in which 15 people belonging to the Afro-descendant community participate and dedicated to the protection and conservation of the 3 species of sea turtles that nest on this beach. For almost 15 years they have protected more than 80% of olive ridley turtles and more than 90% of leatherback and black turtle nests. Unfortunately, this community continues to face the illegal taking of nests and the killing of adult turtles by people from surrounding communities who sell eggs, meat and other derivatives such as turtle blood and oil for consumption. Additionally, there are a large number of dogs on this beach, which prey on the nests, hatchlings and can considerably injure some adult nesting turtles. Billion Baby Turtles is supporting this project with US $4,000, and expects to help almost 40,000 baby turtles to get to the ocean.

Galapagos, Kingdom of Reptiles Part III: Isabela & Santa Cruz

Our short flight to Isabela took longer to check our bags than the duration of the flight. But as we landed, we were treated to a rare overhead view of the dried lava fields of this extraordinary island. After dropping our stuff at our hotel, we boarded our boat to head for the one hour journey to Tuneles, one of the most extraordinary locations on the islands.

The water conditions were a bit rougher than normal and the tide was high but our captain felt the entry was safe so we made our way to the entrance. This otherworldly land and seascape was only recently opened to travelers, previously it was a fishing spot but now fishermen have been hired to bring people to this special place. As we enter the area, we marvel at a small rock outcropping full of Galapagos penguins & blue footed boobies. The lava tunnels offer a view down into the water as turtles and fish pass by while blue footed boobies perch next to giant cacti.

After a short walk to take this place in, we enjoyed lunch on our boat and then headed to nearby El Finado for snorkeling. With the high tide, the first area we moved through had low visibility but we were still able to see several turtles (one nestled in some mangrove roots), as well as black tip reef sharks and a group of five spotted eagle rays. But as we passed through the mangrove, the water became much clearer and more green turtles came into view with every turn around the area. We were also treated to a group of white tip reef sharks hiding out in a cave.

The next morning, we headed away from the water to hike up to the crater of the Sierra Negra volcano, one of five active volcanoes on the island and the largest. Cool misty clouds greeted us as we got off the bus and started uphill. We were treated to several sightings of vermillion flycatchers, a brilliant red bird. As we got to the viewpoint, the dense clouds blocked our view of the crater but Pablo regaled us with stories of past eruptions.

Tortoise at Campo Duro

Plants our group planted to feed future tortoises at Campo Duro

On the way down, we stopped at Campo Duro, an agrotourism project that is participating in a tortoise reintroduction program. Our group had a wonderful lunch with food grown on the farm and then helped to plant tubers to feed the next group of tortoises that come through from the national park as they transition to the wild from the breeding center. We visited two adult tortoises that were not releasable live here and then took a tour of this unique farm.

On our final full day on Isabela, we split our time between land and sea. First, we explored the nearby mangrove estuary. Among the birds and mangroves, we saw a wild tortoise munching on plants; the local population is part of the reintroduction program helping to bring this species back. We also saw a couple of incredible marine iguanas lounging on the road, peeked into a lava tunnel, and heard stories of local history. That afternoon, we hopped on sit-on-top kayaks to explore the islands around Tintoreras across from the town. A gentle paddle offered a unique view of these islands and we spotted more penguins, boobies, and turtles along the way.

Feeding tortoise

Marine reptile posing

Before we caught our ferry to Santa Cruz, we headed to explore Tintoreras by foot and snorkel. First we took a short walk on one of the islands to learn about the marine iguanas nesting here and the lava formations of the island. As we walked to an overlook over a narrow shallow channel, we spotted a couple of white tip reef sharks (who the area is named after) lounging on the bottom (apparently not all sharks need to swim continuously). A curious sea lion came barreling into the far end of the channel heading straight for the sharks. He nipped at the sharks, sending them into a tizzy and then zipped back off, apparently just messing with them for fun! Our excursion ended with our final snorkel. Our first treat there was a seahorse, hanging tight to a drowned branch. That was followed by a bunch more sea turtles as we made our way around the island, the perfect way to end our stay on Isabela.

White tip reef shark

That afternoon, we caught the ferry to Santa Cruz Island, the most populous of the islands, for a two-hour ride. We had a bit of free time to explore before dinner and then met up for the nicest dinner of the trip at a beautiful restaurant overlooking the water. On our last morning, we took a tour of the Charles Darwin Research Station to learn about the organization’s efforts to restore the island’s tortoise populations. We got our first view of the unique saddleback tortoises with their interesting carapaces, along with many hatchlings. We also paid homage to the resting place of Lonesome George, the last known individual of the Pinta Island sub-species, the most famous Galapagos tortoise.

As we headed off in our different directions home or on further travels, we shared stories of our favorite parts of the trip. Over the week, we saw dozens of sea turtles, hundreds of sea lions, wild and human-bred tortoises, many species of birds, along with sharks, iguanas, rays, and many other animals. Our appreciation for the unique forces that created this wildlife paradise and the efforts it takes to protect it only grew as we traveled.

Learn more: Galapagos Turtles & Tortoises Conservation Trip

Galapagos, Kingdom of Reptiles Part II: San Cristobal

Be sure to read Part 1:Pre-Trip Adventures here first.

Our Galapagos Turtles & Tortoises group arrives a day later, a bit groggy from the early flight from Quito but excited to reach this dream destination. We meet our guide Pablo from Galakiwi and immediately we are taken in by his passion for this incredible place. After a delicious buffet lunch and time to rest at our rooms, we take a short ride to the national park interpretive center, walking through the volcanic landscape surrounded by giant cacti, Palo Santo trees, and lava rock.

Pablo takes us on a mesmerizing journey, explaining the natural forces that make these islands so special: the volcanoes that birth the islands as tectonic plates shift and the currents coming from both the north and south – an effect of being located on the equator. These currents brought much of the life that can be found now on the islands, often stowaways on debris floating from the mainland or long flights from the mainland. Due to these factors, the islands have a high degree of endemism (plants and animals that can only be found here) but not a wide variety of biodiversity (the number of different species that inhabit the islands).

Lookout at the top of Frigatebird Hill

View of Darwin Bay

From there, we head up over Frigatebird Hill (Tijeretas) to get a view of the town and Darwin Bay below. We put on our wetsuits (the water was a bit chilly but not too frigid), and carefully made our way around the sea lions occupying the stairs into the bay to head out for our first group snorkel. Winding our way around the bay, we saw a couple of turtles and sea lions swam around us. Finally, we headed back to town, walking along paths through the forest and past Carola Beach, where we caught the last of a beautiful sunset.

Our group’s first full day started with a visit to USFQ to learn about the research of Juan Pablo and Daniela and for a lesson on sea turtle identification, using an online database called Internet of Turtles. We learned about some of the fascinating aspects of sea turtles around the islands, such as orca’s being one of their primary predators, seen in few other places worldwide. Juan Pablo also talked about his research on plastic pollution washing ashore, likely from international fishing boats outside of the marine reserve, as the islands have strong plastic recycling and reduction programs. We also learned about the two types of green turtles living around the islands, the black turtle, a sub-species of green turtle, and what is locally called the yellow turtle or Indo-Pacific green turtle, which are the greens that you can find around the world.

Black turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizi)

Indo-Pacific green turtle (Chelonia mydas)

That afternoon, we returned to Loberia Beach with our group for a snorkel and a coastal walk. A local scouts group joined us for a short beach cleanup activity, a fun way to get to know some of the members of this community. At Loberia, we saw several green turtles, capturing some great images to be able to identify these turtles and several species of fish. Dinner that night was at a great restaurant called Umami located next to the incredible sea lion beach.

Our group next spent a day inland, heading up into the highlands of Santa Cruz to visit El Junco, the only freshwater lake in the islands. After a hike up a steep hill to the crater, we learned about the geology of the island and how the waters impact the community below. Next we headed down to the Galapaguera for our first meeting with the incredible tortoises that these islands are named after.

The hike up to El Junco

Captive reared tortoise at the Galapaguera Breeding Center

This breeding facility helps to repopulate the island’s San Cristobal tortoise population. We strolled through the lowland forest and saw the hatchlings and young turtles in enclosures with many larger tortoises wandering the grounds, growing there for several years before being released into the wild. We then stopped for lunch at a great family restaurant with a tremendous view of the island. We were fed with food grown on this beautiful farm, trying several new dishes and learning about farming in such a unique place.

We saved the best for the last day on San Cristobal, heading out early this today to take the boat ride to Kicker Rock (also known as Leon Dormido for its shape of a sleeping lion). The hour long boat ride on a lovely catamaran was relaxing as we spotted manta rays jumping in the distance. We pulled up along the island and did a circumnavigation on the boat, spotting blue footed and Nazca boobies and learning how this rock was formed.

View of Kicker Rock (aka Leon Dormido)

Black turtle at Kicker Rock

We then donned our wetsuits and hopped in the water, snorkeling along the wall which was speckled with coral and colorful fish. Within a few minutes, we spotted our first black turtle swimming by. As we rounded the end of the rock, more turtles came into view. And then more turtles, at least 10 hanging around the spot. Capturing as many as we could for photo ID, we lingered at this spot as long as we could, marveling in the moment. We rounded the rock to enter the canal between the front part of the rock and the main part, spotting a few black tip reef sharks and sea lions. Passing through the channel seemed to be the hotspot for spotted eagle rays, gliding back and forth underneath us like graceful shadows.

The euphoria on everyone’s face as we left the water was one of the highlights of the trip for me. I love seeing turtles, but I might love seeing the joy they bring to others even more. The boat then took us over to Manglecito, a small bay and beach with mangroves, to eat lunch on the boat and then explore the area.

Part of the group took a boat ashore to walk on the beach and another group hopped in the water to look for more turtles (guess which group I joined?). The water was a bit more clear and much warmer in this shallow area and it didn’t take long at all to find more turtles, these being greens, feeding on algae along the rocky shallows. Again, one turned into three, into eight, ending up with at least another dozen turtles added to our list.

These turtles are so relaxed around people, the result of decades of protections here. They just chomp away or swim casually by, definitely not the norm for where our trips go, mostly places where there is still significant illegal hunting. To cap off the incredible day, I hear our trusty guide assistant Sebastian calling, alerting us to our first swimming marine iguana (we had seen many but not in the water). Returning to town, after a shower and down time, we had a change of pace for dinner, eating a delicious Italian meal at Guiseppe’s, one of the best restaurants in town, to celebrate the incredible day. We went to bed early tonight to rest up for our early flight to our next stop, Isabela Island.

Learn more:

Galapagos, Kingdom of Reptiles: Part 1: Pre-Trip Adventures

I’ve seen many turtles in the water and on the beach in my career. I’ve seen loggerhead turtles fight with fish for lobster heads and leatherback turtles go the wrong way up a freshwater creek. I’ve seen mating and feeding from above and nesting close up. But I’ve never seen anything like what I saw at Loberia Beach on one of our first days in the incomparable Galapagos Islands – a sea lion playing with a turtle like it was its toy.

My partner and I arrived a few days early to explore San Cristobal before the group coming on our Galapagos Turtles & Tortoises trip arrived to get to know the town of Puerto Baquerizo Moreno and ease into the trip. This was my first time to this island, our previous trip only visited the islands of Isabela and Santa Cruz. Upon arrival, we made our way to the home of my friend Juan Pablo Muñoz and Daniela Alarcon, marine biologists working at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, an Ecuadorean university that has a research station on the island.